InThePastLane January 1, 2013 by Edward T. O’Donnell

As sports fans across the nation await the big NCAA college football national championship on January 7, 2013, it’s worth exploring the origins of the teams’ names. The University of Alabama’s team name—The Crimson Tide—originated by chance in the wake of an epic 1907 game against arch rival Auburn. But Notre Dame? How on earth did a college with a French name in the rural Midwest, far from the big cities with large Irish populations, come to be known as “The Fighting Irish”? The answer reveals a great deal about the struggle for ethnic and religious acceptance in United States history, for Notre Dame originally opposed the name due to its potentially negative connotations and only embraced it in 1927, long after it had emerged a national powerhouse in football.

Notre Dame’s humble origins in 1842 are captured in its original Log Chapel. The University maintains a replica on its campus.

First, a little background. Given Notre Dame’s early history, few would have predicted the eventual nickname Fighting Irish. Notre Dame, as its name suggests, was founded in 1842 by a group of French-speaking priests of the Congregation of the Holy Cross. Situated in South Bend, Indiana, it drew Catholic students of all ethnicities from throughout the Midwest. As Catholic colleges went, Notre Dame soon became one of the best, establishing the first Catholic law school in 1869 and first Catholic school of engineering in 1873.

It is important to note that in this late-19th century period Catholic colleges like Notre Dame, Fordham, Boston College, Georgetown, and College of the Holy Cross represented Catholic—in particular Irish Catholic—upward mobility and yearning for acceptance. Mass immigration since the 1830s had only recently created a sizable Catholic population in the United States, a development most native-born American Protestants viewed with alarm and anger. Anti-Catholicism and anti-Irish sentiment soared and remained a prominent feature of public life until the early 20th century [click here for many examples].

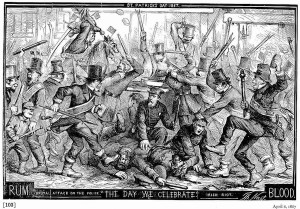

Political cartoonist Thomas Nast routinely depicted the Irish as savage brutes in the pages of the nation’s most popular journal, Harper’s Weekly. This image, published April 6, 1867, portrays St. Patrick’s Day as a bloody melee.

Take, for example, the assessment of a young Theodore Roosevelt in the 1880s that, “The average Catholic Irishman of the first generation, as represented in the [New York State] Assembly [is a] low, venal, corrupt, and unintelligent brute.” Or Harper’s Weekly a few years earlier: “Irishmen…have so behaved themselves that nearly seventy-five per cent of our criminals and paupers are Irish; that fully seventy-five per cent of the crimes of violence committed among us are the work of Irishmen; that the system of universal suffrage in large cities has fallen into discredit through the incapacity of the Irish for self-government.” In short, most Americans viewed Irish Catholics as people prone to violence, crime, corruption, drunkenness, and ignorance. They also viewed them as members of a church that was both wrong theologically and scheming to overthrow the American republic. One of the primary goals behind the founding of so many Catholic colleges in this period, therefore, was to improve the reputation of Catholics in the U.S. by minting generations of respectable, educated, and successful Catholic men.

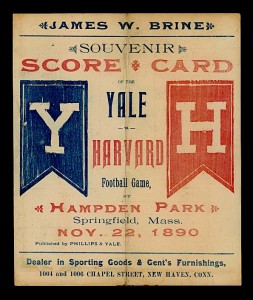

A scorecard from the Harvard-Yale football game of 1890. Rivalry games such as this drew enormous crowds at the turn of the century.

Notre Dame went about this work in relative obscurity until the emergence of college football in the 1880s and 1890s as America’s second most popular sport (after professional baseball). In an era before radio and television (not to mention fire codes), it was not uncommon for 30,000 fans to turn out for games between Harvard and Yale, or Army and Navy. They were the powerhouse teams that Notre Dame eyed as it began its rise. In the eyes of ethnic Catholics, these schools stood as bastions not only of football prowess, but also of elite Protestant privilege. As such they became irresistible opponents for Notre Dame.

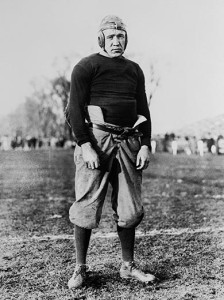

Knute Rockne first earned fame as a player for Notre Dame, He later took over as coach and led the team to four national championships.

Notre Dame’s football program started in 1887 and gained national recognition by the early 20th century. A stunning victory over Michigan in 1909 paved the way for contests against other top-level teams. Notre Dame’s breakthrough moment came in 1913 when, led by captain Knute Rockne, it upset Army 35-13. The game is considered one of the most important in college football history because it was the first time a team made extensive (17 attempts) and successful (14 completions and two TD’s) use of the little-used forward pass. Rockne took over as coach in 1918 and guided the team to a succession of winning seasons, including national championships in 1919, 1924, 1929, and 1930.

In 1924 famed sportswriter Grantland Rice dubbed the four members of Notre Dame’s extraordinarily successful backfield The Four Horsemen.

By the mid-1920s, Notre Dame was by far the best-known Catholic university in the nation. As a consequence, it was the first college football team with a truly national following as Catholics from Baltimore to Boise to Berkeley adopted the team as their own even if they never attended Notre Dame. These fans, known as “subway alumni,” might root for Georgetown or Holy Cross as their local favorites, but they avidly read the details of Notre Dame’s exploits in the Sunday sports sections. Irish Catholics especially identified with the David and Goliath quality of Notre Dame’s rise. As a group, Irish Catholics had begun by the 1910s and 1920s to earn a measure of success and acceptance in a nation long hostile to Catholics. As they did so, they took enormous pride in the ability of Notre Dame to knock off teams like Princeton and Army. Keenly aware of this phenomenon, Rockne and his successors made it a policy (which stood until 1975) never to play the other top Catholic college teams.

The team’s success and national reputation increased the pressure on the school to adopt an official nickname. In the early days of intercollegiate sports, college teams had no nicknames; they simply played as Harvard, Northwestern, or USC. But by the 1920s teams began to take on nicknames, often courtesy of sportswriters who were always eager to apply a catchy appellation. Most colleges were slow to choose an official name, but as time passed it became clear that they risked having sportswriters or students giving a less-than-suitable name to a college.

Georgetown, for example, gained its name “Hoyas” when its students took to chanting “hoya saxa!” at games—a mixed Greek (hoya) and Latin (saxa) phrase that translates as “what rocks!” The phrase might have referred broadly to the stalwart quality of Georgetown’s defensive line, but—students being students—likely referred more crudely to the players’, shall we say (ahem), testicular fortitude.

During its rise to national prominence, Notre Dame had been called many names, including simply the “Catholics,” but also the “Horrible Hibernians” and a host of other undignified appellations. The first known reference to the team as the “Fighting Irish” occurred in the Detroit Free Press in 1909, but the name failed to stick. Other nicknames like “Gold and Blue” came and went, as did the “Warriors” and “Ramblers.” But in 1919, perhaps inspired by a visit to Notre Dame by Eamon de Valerra, one of the key revolutionaries working to achieve Ireland’s independence, the name “Fighting Irish” returned as a favorite nickname among the school’s students. Rockne soon began using the name when talking to the press.

The turning point in the story came in 1925 when Notre Dame graduate Francis Wallace, then a sportswriter for the New York Post, began referring to the team as the “Fighting Irish” in his coverage of college football (his first choice was “Blue Comets” but that had not stuck). In 1927 Wallace moved to the New York Daily News, one of the largest circulation papers in the nation and before long the name Fighting Irish was known coast to coast.

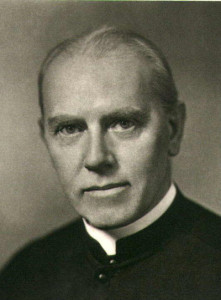

Rev. Matthew Walsh, CSC, Notre Dame’s 11th President who in 1927 set aside his reservations and gave official sanction to the name, “Fighting Irish” for the university’s sports teams.

But it still lacked official sanction from school officials. Understandably, Notre Dame President Fr. Matthew Walsh, C.S.C and other school officials were leery of the name. It conjured up the longstanding stereotype that the Irish were prone to fighting and violence—the very stereotype Catholic colleges were committed to eradicating.

Yet there was something attractive about the name in a society that worshiped competitiveness and a fighting spirit. Perhaps, if properly presented, the name might make the American public think of the great contributions made by the Irish Brigade in recent wars, rather than the many riots of the nineteenth century in which Irish immigrants played a prominent role.

Notre Dame’s President Walsh was inclined toward this more optimistic interpretation and so when a reporter from the New York World wrote him a letter in the fall of 1927 seeking his opinion on the popular name, Walsh responded:

The University authorities are in no way averse to the name ‘Fighting Irish’ as applied to our athletic teams… It seems to embody the kind of spirit that we like to see carried into effect by the various organizations that represent us on the athletic field. I sincerely hope that we may always be worthy of the ideals embodied in the term ‘Fighting Irish.’

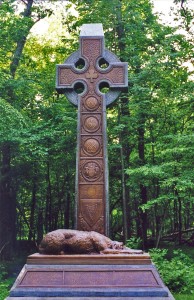

The valor displayed by Irish regiments, most famously The Irish Brigade, in the Civil War, Spanish-American War, and World War I helped improve the reputation of the Irish in America.

That settled it. The fact that many of the football team’s players were not Irish (some weren’t even Catholic), generated a few raised eyebrows. But Knute Rockne defended the name: “They’re all Irish to me. They have the Irish spirit and that’s all that counts.”

The rest is history. The University of Notre Dame went on to win national championships (in addition to earlier ones in 1919 and 1924) in 1929, 1930, 1943, 1946, 1947, 1949, 1964, 1966, 1973, 1977, 1988 for a total of 13 (some say 15, but you’ll have to look up the seasons of 1938 and 1953 to get the details).

In recent years, with teams under pressure from various interest groups to drop names like Redmen and Warriors, one occasionally reads of a movement among some Irish Americans urging Notre Dame to adopt a new name (or at least to get rid of the pugilistic Leprechaun logo and mascot). But even with a team comprised of only a handful of Irish Americans, don’t expect any change soon. The faithful wouldn’t hear of it.

You can follow me on Twitter @InThePastLane

Sources and Further Reading:

Jay P. Dolan, The Irish Americans: A History (Bloomsbury Press, 2010)

John Heisler and Tim Prister, Always Fighting Irish: Players, Coaches, and Fans Share Their Passion for Notre Dame Football (Triumph Books, 2012)

Kevin Kenny, The American Irish: A History (Oxford, 2000)

Jim Lefebvre, Loyal Sons: The Story of the Four Horsemen and Notre Dame Football’s 1924 Champions (Great Day Press, 2008)

Charles Morris, American Catholic: The Saints and Sinners Who Built America’s Most Powerful Church (Vintage, 1998)

Ray Robinson, Rockne of Notre Dame: The Making of a Football Legend (Oxford, 2002)

Murray A. Sperber, Shake Down the Thunder: The Creation of Notre Dame Football (Holt, 1993)