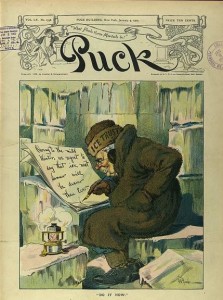

Headlines warning of an impending “ice famine” were common in the 19th and early 20th century during warm winters (NYT Feb 2, 1906)

What on earth is an “ice famine”? Well, if you were alive in the nineteenth century and the U.S. was experiencing winter as mild as this one in 2012-2013, the newspapers would be full of stories about a potential “ice famine.” The problem was not a shortage of ice in January and February, but rather in the coming summer because Americans, especially city dwellers, had come to depend on massive winter harvests of natural ice from ponds, lakes, and rivers to cope with summer heat and preserve their food. The creation of this ice industry is one of the more fascinating stories of American entrepreneurship. It’s also a story of a remarkable transformation of the American diet.

What on earth is an “ice famine”? Well, if you were alive in the nineteenth century and the U.S. was experiencing winter as mild as this one in 2012-2013, the newspapers would be full of stories about a potential “ice famine.” The problem was not a shortage of ice in January and February, but rather in the coming summer because Americans, especially city dwellers, had come to depend on massive winter harvests of natural ice from ponds, lakes, and rivers to cope with summer heat and preserve their food. The creation of this ice industry is one of the more fascinating stories of American entrepreneurship. It’s also a story of a remarkable transformation of the American diet.

In an age of ubiquitous air-conditioning and refrigeration, it’s hard to comprehend just how much 19th-century Americans depended on ice. By the 18th century, icehouses were standard features on most estates in Europe and even Colonial America, but for the common man and woman, especially in cities, ice in warm weather was as rare and expensive a commodity as caviar.

Frederic Tudor, the man known as the “Ice King” for his role in creating the American commercial ice industry.

That began to change in 1806, when an ambitious Massachusetts man named Frederick Tudor set out to single-handedly create the world’s commercial ice industry. After a trip to the tropics he became convinced that people in warm climates, whether Charleston, SC or the Caribbean, would pay good money for New England ice. And New England had a lot of ice. And it was free. The only costs – and the biggest challenges for this would-be business – was harvesting, transporting, and storing it.

Tudor was the charismatic son of a wealthy family. He was 23 years old and possessed an almost evangelical commitment to the enterprise. “People believe me not when I tell them I am going to carry ice to the West Indies,” he confided in his diary.

Actually, people greeted the idea not only with incredulity, but also laughter. As Tudor wrote, his plan “excited the derision of the whole town as a mad project.” Even his father called the scheme “wild and ruinous.”

But Tudor remained undaunted. He bought a ship, filled its hold with 130 tons of ice cut from a Massachusetts pond, set sail for the Caribbean island of Martinique. The snickering now spread from his home town to Boston. The Boston Gazette reported with glee: “No joke. A vessel with a cargo of ice has cleared out from this port for Martinique. We hope this will not prove to be a slippery speculation.”

Tudor’s first foray into the ice industry brought mixed results. The good news was that most of the ice survived the voyage. The bad news was that there were no ice houses in Martinique. So Tudor lost more than $4000 – a huge sum at the time.

But the next year he was back at it, sending in 240 tons of ice to Havana, Cuba in 1807. He managed to break even on this venture, but he would have to find a way to earn a profit – and soon.

The next few years saw more voyages and some success. But then bad luck and a theft by a corrupt business partner plunged Tudor into poverty and two stints in debtor’s prison in 1812 and 1813.

As soon as Tudor was released, however, he was back at his ice venture. He convinced partners in southern US cities and the tropics to build icehouses. This ensured that his cargo would not melt upon arrival. Tudor also experimented with different forms of insulation to reduce melting in icehouses and on board ships. He eventually discovered sawdust from saw mills. Sawdust was plentiful and practically free – and it was a terrific insulator for ice.

By the early 1820s, Tudor was enjoying modest success. But the market for ice remained small.

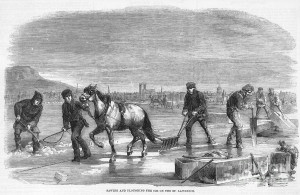

Ice cutting devices like this allowed for the harvesting of uniform blocks of ice. It was much easier than the earlier method of cutting blocks with saws.

Then in 1825 he teamed up with Nathaniel Wyeth, one of his ice suppliers, who had invented dual blade ice cutter pulled by horses across ponds, lakes, and rivers. This device – a kind of mechanical reaper for the ice industry — cut a grid of uniform grooves in the ice. Then workers using iron bars pried loose identical blocks of ice. This method proved far more efficient than the traditional method of cutting irregular ice blocks with saws. And the harvested blocks could be stacked neatly for more efficient transportation and far less melting. Soon Tudor had tripled his production and profits rose accordingly.

In 1833 Tudor sent 180 tons of ice 16,000 miles from Boston to Calcutta, India. Very little ice melted en route and the ship’s arrival touched off a frenzy for ice. Soon a group of investors constructed an icehouse to receive future shipments of Tudor’s ice. In the coming years Tudor – now known as “The Ice King” – sold ice harvested in Massachusetts all over the world. By 1856 ships leaving Boston carried 150,000 tons of ice to US ports and 43 nations around the world.

Here’s an amazing statistic that you can use to win a bar bet: What product (by weight) was the #2 US export in the 1850s? Cotton was #1 and ice was #2!

But no people in the world fell in love with ice more than Tudor’s fellow Americans. The tonnage of ice sold by Tudor and a growing number of competitors soared in the 1840s and 1850s. The greatest demand came from American cities. English novelist and travel writer Fanny Trollope toured the US in the early 1830s and later wrote in her book, Domestic Manners of the Americas, “I do not imagine there is a home without the luxury of a piece of ice to cool the water and harden the butter.” Demand for ice grew so rapidly that by 1855 residents of New York City were consuming 285,000 tons annually.

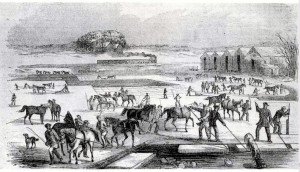

Where did this ice come from? By the 1850s the ice industry in New England and New York employed thousands of men – many of them farm hands and

Ice harvesting in the mid-19th century required new technology and lots of horse-power and human labor.But no people in the world fell in love with ice more than Tudor’s fellow Americans.

lumberjacks looking for work in the winter months – to harvest vast quantities of ice from ponds, lakes, and rivers. Some ice was floated on barges to big icehouses in cities, but by the 1850s more and more ice was moved in railroad cars.

No body of water was off limits to the icemen, not even Henry David Thoreau’s famed Walden Pond. In 1846 Thoreau noted in his journal that a team of burly Irish immigrants had descended on the pond to harvest as much as 1000 tons of ice per day. Thoreau was irked by the noise, but he was also impressed by its implications: “The sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and Calcutta drink at my well.”

Frederick Tudor, “The Ice King,” died a very wealthy man in 1864. By this time it was clear that his efforts to make ice cheap and plentiful meant more than simply providing Americans with cool drinks in the summer. Ice had begun to change Americans’ basic diet. Whereas before 1830 much of the typical Americans’ diet consisted mainly of bread and dried or salted meat, after 1830 it included increasing amounts of fresh fruit, vegetables, meat, fish, and dairy products. This improvement in the variety and quality of food benefited public health and extended life expectancy. Ice also led to the popularity of products like ice cream. Once the rarest of treats, ice cream became so popular that in 1850 a leading women’s magazine declared it a basic necessity of life.

No body of water was off limits to the icemen, not even Henry David Thoreau’s famed Walden Pond. In 1846 Thoreau noted in his journal that a team of burly Irish immigrants had descended on the pond to harvest as much as 1000 tons of ice per day. Thoreau was irked by the noise, but he was also impressed by its implications: “The sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and Calcutta drink at my well.”

The availability of cheap and plentiful ice meant more than cool drinks in the summer; it changed Americans’ basic diet. Butchers, fishmongers and dairymen began to use ice to preserve their stocks, leading to significant improvement in food quality and public health. Ice also greatly increased the diversity of culinary offerings available to Americans as importers found ways to preserve previously exotic delights like freshwater fish. Ice cream, once the rarest of treats, became so popular that in 1850 a leading women’s magazine declared it a basic necessity. Ice likewise made possible cold beer and other alcoholic drinks. Temperance advocates, however, countered with “Moderation Fountains” during heat waves that provided free ice water as an alternative to the offerings of a city’s countless saloons.

The availability of cheap and plentiful ice meant more than cool drinks in the summer; it changed Americans’ basic diet. Butchers, fishmongers and dairymen began to use ice to preserve their stocks, leading to significant improvement in food quality and public health. Ice also greatly increased the diversity of culinary offerings available to Americans as importers found ways to preserve previously exotic delights like freshwater fish. Ice cream, once the rarest of treats, became so popular that in 1850 a leading women’s magazine declared it a basic necessity. Ice likewise made possible cold beer and other alcoholic drinks. Temperance advocates, however, countered with “Moderation Fountains” during heat waves that provided free ice water as an alternative to the offerings of a city’s countless saloons.

Ice also delivered an impressive array of medical benefits. Doctors at hospitals soon discovered that ice could save lives and began prescribing it as a means of lowering the body temperature of fever victims, especially the young. During the summer, city hospitals issued free ice tickets to the poor, and crowds often grew so anxious outside free ice depots during heat waves that free-for-alls known as ice riots erupted. According to an account in The New York Times of one incident in July 1906, “a woman pulled a man’s mustache and another woman hit a man with a dishpan,” and within minutes, “the ice was scattered on the sidewalk and hundreds were engaged in a rough-and-tumble fight.”

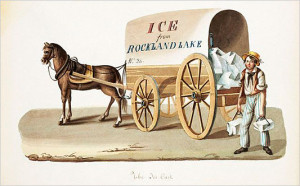

By the 1880’s, about 1,500 ice wagons plied the streets of New York City every day. The burly, typically Italian iceman, a huge block of ice slung over his back and gripped with a pair of tongs, became as familiar a fixture on the urban landscape as the Irish beat cop.

During a typical week in the 1880’s, an iceman might deliver as much as 80 tons of ice, much of it carted up multiple flights of narrow and rickety stairs. The iceman’s daily interactions with housewives gave rise to countless bawdy jokes, an occurrence immortalized in Eugene O’Neill’s drama “The Iceman Cometh,” set in 1912.

While urban Americans clearly loved their ice—Manhattan and Brooklyn consumed 1.3 million tons in 1879 (more than a quarter of the national market)—they often loathed the companies that provided it, and in the 1880’s and 1890’s, a rising chorus of critics charged firms with price gouging and monopolistic practices. Ice companies tried to blamed summer price increases on mild winters that produced insufficient stocks–the aforementioned “ice famines.”

That claim didn’t work in 1896 when in New York City the city’s ice firms were absorbed into a massive national ice trust called the Consolidated Ice Company. Prices jumped 33 percent that spring, and more than doubled by midsummer. Hardest hit were the poor, who could afford to buy their ice, like their winter coal, only in small quantities.

Anger against ice companies persisted after 1901. Here an ice baron sits in an ice house wearing a hat labeled “Ice Trust” and writing, “Owing to the mild winter, we regret to say that ice next summer will be dearer than ever.”

Popular outrage reached new heights four years later in 1901 when investigative journalists revealed that Mayor Robert Van Wyck and other city officials had conspired to create a virtual monopoly for Consolidated. As the price of ice doubled, new revelations showed that the mayor and his brother had been given $1.7 million in Consolidated stock. The investigations produced no convictions, but the mayor, hounded by catcalls of “Ice! Ice! Ice!” whenever he appeared in public, was soundly defeated by a reform ticket in the election of 1901.

America’s ice age, however, was brought to a close not by reformers but by inventors who developed refrigeration and ice-making machinery. As early as the 1870s large brewers had begun to rely on mechanical refrigeration. Soon the meatpacking industry joined them. By 1900 refrigeration machinery was widely available. So, too, was ice making machinery. The final step came with the introduction of electric home refrigerators. By 1950 the iceman had been become as much a relic of a long-ago age as the blacksmith and the lamplighter.

I invite you to follow me on Twitter @InThePastLane

Sources and Further Reading:

Oscar Edward Anderson, Jr. Refrigeration in America: A History of a New Technology and Its Impact (Princeton University Press, 1953).

Mariana Gosnell, Ice: The Nature, the History, and the Uses of an Astonishing Substance (Knopf, 2005)

Jonathan Rees, The Cold Chain: A History of Ice and Refrigeration in America and the World, forthcoming, John Hopkins University Press.

Carl Seaburg and Stanley Paterson, The Ice King: Frederic Tudor and His Circle (Massachusetts Historical Society and Mystic Seaport, 2003).

Gavin Weightman, The Frozen-Water Trade: A True Story (Hyperion, 2003)