[Note: a version of this piece originally ran in the Huffington Post on April 23, 2016; You can also hear this and related pieces in Episode 010 of my podcast, In The Past Lane]

The recent announcement by the United States Treasury Department that Harriet Tubman, escaped slave and abolitionist, would replace President Andrew Jackson on the $20 bill has garnered a lot of attention. Tubman will not only be the first African American to appear on U.S. currency, she also will be the first woman to do so in more than a century (Martha Washington and Pocahontas made cameos in the late-19th century). Meanwhile, Jackson will be demoted to the backside of the $20. Predictably, conservatives and traditionalists filled the Twittersphere and other forms of social media with outrage against what they see as the latest affront by the forces of so-called “political correctness.”

The recent announcement by the United States Treasury Department that Harriet Tubman, escaped slave and abolitionist, would replace President Andrew Jackson on the $20 bill has garnered a lot of attention. Tubman will not only be the first African American to appear on U.S. currency, she also will be the first woman to do so in more than a century (Martha Washington and Pocahontas made cameos in the late-19th century). Meanwhile, Jackson will be demoted to the backside of the $20. Predictably, conservatives and traditionalists filled the Twittersphere and other forms of social media with outrage against what they see as the latest affront by the forces of so-called “political correctness.”

While this response is understandable – people often see change as a form of loss – it’s also misguided. One of the central insights gained from the study of history is that, Nothing has always been. Nothing. Everything that we think of as traditional, has a point of origin that is probably not as far back in time as you think. For example, when did the United States decide it needed a massive peacetime military – you know, two million soldiers and 500 ships? The year was 1950 – less than 70 years ago. Before 1950, Americans agreed that a republic ought to have a small peacetime military. Then the Cold War happened and we changed our mind. There are countless other examples, but you get the point.

So how does this apply to the new $20 bill? First, we didn’t even have federal paper money until 1862 – that’s 74 years AFTER the ratification of the US Constitution. And second, in the coming years, many, many faces appeared on that paper money. Before Jackson, President Grover Cleveland’s face appeared on the $20 bill. Jackson bumped him in 1928 – a mere 88 years ago. Let’s face it: the look of US paper money has changed many, many times and it wasn’t designed by God or George Washington.

President Grover Cleveland graced the front of the $20 bill until he was displaced by Andrew Jackson in 1928.

But the negative reaction to the new $20 bill also reflects more than mere nostalgia. It indicates a shallow understanding of the purpose of civic symbols. Choosing names for public schools, establishing holidays, and building monuments to people or events are ways a society proclaims and affirms certain values. The selection of particular people to adorn U.S. currency performs a similar function. It says, in so many words, these people and what they stood for and what they did are worthy of our admiration. Their examples from the past should inspire us as we go about living our present and building our future.

Jackson was known popularly as “Old Hickory” and enjoyed a reputation as a defender of the “common man.”

This understanding explains the decision to demote Andrew Jackson from his place of honor on the $20 bill. Simply put, American values have changed a lot since his presidency (1829-1837) and since his placement on the $20 bill in 1928. In his day and for decades thereafter, Jackson was hailed as a man who expanded American democracy and defended the rights of the “common man” against the predations of the rich and politically connected.

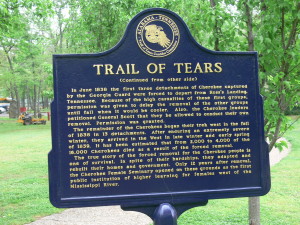

These are very important accomplishments and this aspect of Jackson’s reputation is largely accurate. But it’s also incomplete. It obscures the fact that in Jackson’s understanding, democracy and equal rights only applied to white men. And it ignores the fact that Jackson advanced the cause of white men by promoting the expansion of slavery. Key to this policy was the opening of vast stretches of the American southeast to whites for cotton cultivation by enslaved labor. Jackson achieved this goal by forcibly expelling – in defiance of the U.S. Supreme Court – tens of thousands of Native Americans from their homelands in the American southeast. Their deadly march to Oklahoma killed thousands and became known as the “Trail of Tears.”

Jackson’s expulsion of Native Americans from the US southeast became known as the “Trail of Tears” because thousands dies on the forced march to Oklahoma.

These disturbing facts regarding Jackson’s presidency are not politically correct; they are simply correct and worthy of our attention. Jackson’s heroic status in the nineteenth century reflected the values of an antebellum America that was committed to territorial expansion and slavery. Similarly, the placement of Jackson on the $20 bill likewise reflected the values of a 1920s America that was dedicated to upholding a Jim Crow system of segregation and racial oppression.

A lot of history has unfolded since 1928 and with it has come an expansive notion of American citizenship that includes women, ethnic and racial minorities, immigrants, and members of the LGBTQ community. This transformation has been accompanied by an increased willingness to confront the darker chapters of American history like slavery and Japanese internment.

In light of this development, the choice of Harriet Tubman to replace Jackson is a laudable one. Symbolically, as a woman, an African American, and a former slave, Tubman stands for the Americans left out of Jackson’s vaunted “common man” constituency.

This 1850s woodcut image of Harriet Tubman depicts her as a defiant radical willing to break the law to end slavery.

What’s more, Tubman embodied an essential and often undervalued American tradition of civil disobedience. Every chapter in the unfolding story of American freedom, democracy, and justice has been written by people who were willing to defy unjust laws, despite the attendant risks to their lives, reputations, and property. Tubman escaped slavery and then willingly risked her life innumerable times by returning to the South to guide others to freedom in the North along the Underground Railroad. Like later activists fighting for labor rights, women’s rights, civil rights, and gay rights (just to name a few), she broke laws to expose their unjust character and gain their repeal. What could be more American than that?

Placing Harriet Tubman on the $20 bill reflects an broadened notion of what sort of Americans and what kinds of actions are worthy of our collective admiration and commemoration. It’s no mere coincidence that this has occurred at a time when public sentiment has demanded the removal of pro-Confederate symbols from the public square. And this fact should caution us against reading too much into the new $20 bill. Symbols are important. But they are not ends in themselves. The best ones call to our attention what we value and why.

In 2016 the United States is beset by serious problems concerning poverty, inequality, and racism. Harriet Tubman’s arrival on the $20 bill will not solve these problems. Its purpose is to stand as a vivid and powerful symbol of freedom, equality, and inclusion. It’s up to us citizens to make use of it.