As the citizens of the United States follow this wild and often bewildering presidential primary process, few stop to ask a very important question: why do we have primaries in the first place? In the history of American democracy, political primaries are of relatively recent origin, so when and why did we adopt them?

As the citizens of the United States follow this wild and often bewildering presidential primary process, few stop to ask a very important question: why do we have primaries in the first place? In the history of American democracy, political primaries are of relatively recent origin, so when and why did we adopt them?

Before answering these questions, let’s be clear about one thing: American democracy has changed A LOT over the centuries. Some people find this fact a little disconcerting, since we often take comfort in the notion that amidst the rapid social changes around us, there exist certain constants like the family, religion, language, national identity, and democracy.

But the fact is, as you’ve heard me say many times before, everything changes and evolves, including the family, religion, language, national identity, and yes, good old democracy.

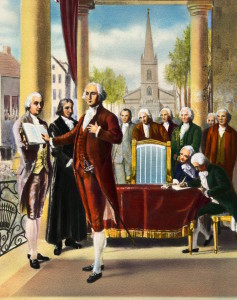

George Washington being sword in as the nation’s first President. He was not elected by popular ballot, but rather by appointed electors.

Just think of the history of American democracy. At the founding of the Republic in the late 18th century most people could not vote and presidents were not elected by the people, but rather by electors. There was no set date for election day. And there were no political parties. In fact, nearly all the founders agreed the political parties were dangerous institutions that threatened to destroy the republic.

Jump ahead 40 years to the 1820s and the situation was very different: nearly all white male citizens have gained the right to vote and Americans have embraced political parties as indispensable features of democracy. Soon came other innovations: paper ballots replaced voice votes and simple shows of hands. Election day became fixed as the first Tuesday that follows a Monday in November. Political parties developed political campaigns, with catchy slogans and songs and rallies and parades to build party loyalty and get out the vote.

Two generations later, the Civil War led to voting rights for black men. Voting rights, of course, that were later stripped away in the Jim Crow era.

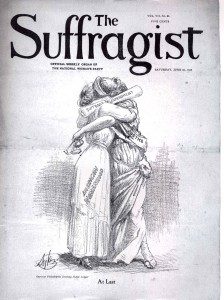

And while that was happening in the early 20th century, women gained the right to vote.

See what I mean? Our democracy has evolved – A LOT — since its creation.

So, when did we add primaries to the mix — and why?

The idea of holding political primaries emerged in the early 20th century, the period known as the Progressive Era. It was promoted by reformers who had come to see the major political parties as powerful and corrupt organizations that controlled the political process in very undemocratic ways for their own benefit. And one of the most important powers they possessed was the power to choose nominees for office, from city counselors all the way up to the president of United States.

The prime example of how all this work was Tammany Hall in New York. Tammany was a powerful political organization that dominated New York politics – and greatly influenced national politics – from the 1860s to the 1930s. You probably know the name, Boss Tweed. He was one of Tammany’s more colorful leaders in its early years. In fact, his nickname – Boss – was a recognition of his power to control politics and elections. It came from his critics, not his Tammany admirers.

The power enjoyed by bosses like Tweed had many manifestations and we will explore them in a future podcast episode on the history of political machines.

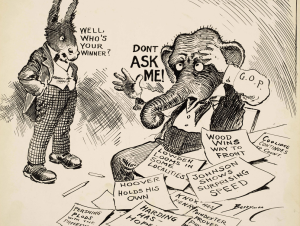

A political cartoon about the prolonged and secret backroom dealing at the 1920 GOP convention that eventually produced Warren G. Harding.

But for today, let’s focus on the power to control the nomination process. Every fall, the leaders of Tammany Hall – and the leaders of every other political party organization across the nation – would gather behind closed doors to choose a slate of nominees for every office being contested that November. The only time the people – the democracy – played a role was on election day when they had the opportunity to choose among candidates selected by a small group of men huddled in proverbial “smoke filled rooms.”

Reformers hated this system because guess who it intentionally shut out? That’s right – reformers. Party officials considered “reform” a dirty word. In fact, Tammany Hall’s unofficial campaign slogan was, ”to hell with reform!” Party leaders liked order, and predictability, and they liked candidates who were loyal and obedient to them, rather than to the public. That’s because party leaders had strong ties to business and banking interests – interests that more often than not the target of reformers.

So reformers who wanted to push for laws to improve public housing, education, or workplace safety, or for policies that would reduce corruption or lower taxes – they were left on the outside looking in. Sure, they could form their own Labor Party or Citizens for Good Government Party, but they stood almost no chance of winning. They could also lobby officeholders to support their reform causes, but few if any officeholders dared risk defying party officials for fear of being denied nomination in the next election cycle. So, listen to the bosses, keep your job. Listen to your constituents, lose your job.

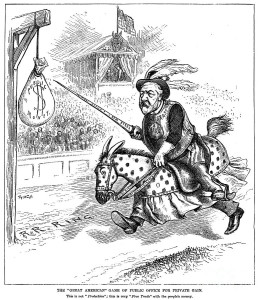

In 1884 Republicans dumped incumbent President Chester A. Arthur in favor of party loyalist James G. Blaine. This cartoon suggests Blaine was not just loyal, but also corrupt.

Party bosses exerted similar control over the selection of delegates to the state and national party conventions that chose presidential nominees. Only party loyalists and stalwarts were chosen, men who could be counted on to vote the way party leaders instructed them based on their wheelings and dealings in those smoke-filled rooms. This fact explains why in 1884 President Chester A. Arthur was denied the Republican party nomination for a second term. Arthur, who has risen to the presidency following the assassination of James Garfield in 1881, had angered Republican leaders by criticizing the party’s corrupt system of awarding political appointments, the so-called “spoils system,” and for promoting civil service reform. So they made certain delegates to the GOP convention in June 1884 dumped President Arthur in favor of a staunch party loyalist named James G. Blaine.

So, how did reformers propose to break this undemocratic stranglehold of political parties on the nomination process?

Primaries. Primaries in which the people could choose the final nominees from a wide open list of candidates. With primaries, the political parties could support their favored candidates, but the ultimate choice of nominee would rest with the people. It would be, Progressive-era reformers claimed, a restoration of democracy in America. We’d once again have a government of, by, and for the people.

Initially, primaries were adopted in local elections for offices like school board and mayor. But they gradually expanded to include nominations for state legislators and governors. By 1915 every state in the country used the primary system for for some or all of its state and local elections.

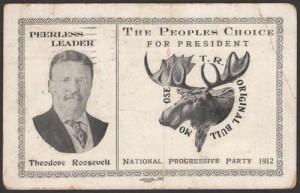

And what about presidential elections? The campaign of 1912 was the first to feature presidential primaries. In that year, 14 states held some form of presidential primary. The purpose of these contests, of course, was not to nominate a presidential candidate, but rather to apportion delegates pledged to support a particular candidate at the later national party conventions.

But in many states, these early presidential primaries were nonbinding. In other words, they gauged public opinion, but delegates were not bound by the results. And, of course, 34 states held no primaries at all. Delegates in those states were apportioned in the old-fashioned way: by state conventions controlled by the political party bosses.

Despite Theodore Roosevelt’s popularity, the GOP chose Taft as its nominee in 1912. Roosevelt then launched his famous Bull Moose campaign.

The weakness of this early primary system was made crystal clear in the very first presidential election to feature political primaries, 1912. This contest was one of the most dramatic in American history. Incumbent President William Howard Taft was challenged for the nomination by two fellow Republicans, Robert La Follette of Wisconsin, and former President, Theodore Roosevelt of New York. Roosevelt was clearly the most popular candidate among Republican voters. He won nine of the 14 presidential primaries, with Taft and La Follette winning just two each. Roosevelt’s victories garnered him 290 delegates versus only 124 for Taft. But Republican leaders favored Taft, and they controlled the delegates in the 34 states that held no primaries. So the less popular Taft received the party’s nomination. Furious, Theodore Roosevelt launched his famous 3rd party “Bull Moose” campaign but came up short in the end.

In the years that followed, presidential primaries increased in popularity. By the presidential campaign of 1916, 25 states held primaries. But then, the major political parties pushed back against the political primary movement, convincing several states to drop them. Primaries, they argued, were expensive and voter turnout was lower than reformers promised.

So by 1936 the number of primaries had declined to only 12 states. And it stayed that way—just 12 states holding presidential primaries—until 1968. That’s less than 50 years ago. So, the presidential primary system, at least as we know it today, is of relatively recent vintage.

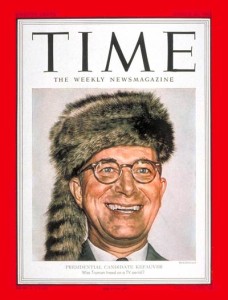

That’s not to say that presidential primaries played no significant role in elections held before the 1970s. In fact, primaries enjoyed a resurgence in popularity and impact after World War II. From 1948 to 1952 voter participation nearly tripled. This upsurge was due in part to new voting rules in many states, but also to the rise of television as a new factor in American politics. Television allowed outsiders and less established politicians to gain popularity which they then could parlay into a bid for the presidency.

Estes Kefauver upset President Harry Truman in the 1952 New Hampshire primary. The victory increased the importance of primaries in the coming years.

For example, in 1950 a relatively little-known senator from Tennessee names Estes Kefauver

became a household name when he chaired televised hearings on the organized crime problem in the US. Two years later in 1952, in New Hampshire’s “first in the nation” primary, Kefauver defeated incumbent Pres. Harry Truman. That result prompted Truman to drop out of the race. 16 years later in 1968, incumbent president Lyndon Johnson’s poor showing in the New Hampshire primary likewise prompted him to withdraw from the race.

While poor showings in primaries doomed Truman and LBJ, strong performance in primaries led John F. Kennedy to his party’s nomination in 1960 and Barry Goldwater to his in 1964.

But it’s after 1968 that presidential primaries began to assume the important role they play today. Rule changes by the Republican and Democratic parties as to how delegates would be awarded to presidential candidates encouraged a growing number of states in the 1970s and 1980s to establish presidential caucuses or primaries. Now every state holds one and they play dominant role in selecting presidential candidates.

But 100 years on, it’s worth asking: have presidential primaries, or at least our current system of presidential primaries, helped or harmed American democracy? Remember, back in the 19 teens when primaries were invented, the goal was to shift power from political party bosses to the people.

Well, many historians and political scientists question whether political primaries actually have improved our democracy. They note, for example, that while primaries have indeed put more power and influence in the hands of everyday voters when it comes to choosing political candidates, over the decades, the Democratic and Republican parties have found many ways to exert tremendous influence over the nomination process. The parties use their enormous financial power and personnel resources to favor particular candidates. And the parties have frequently changed the way delegates are awarded to primary candidates, thereby diminishing the influence of voters.

Critics also argue that political primaries are inherently flawed in terms of representing the views of the general American public. Only a sliver of the electorate participates in political primaries and these voters tend to be more ideologically extreme –– both liberal and conservative –– in their political views. This dynamic can result in the nomination of candidates whose political views are outside the American mainstream and as a result these candidates lose in the general election. The old system of party bosses nominating candidates may not have been very democratic, but it did often ensure the nomination of candidates with broad electoral appeal.

But, people, rest assured, there are many, many proposals out there for reforming both the primary process and elections in general. These range from plan to make it easier to vote in primaries — including proposals to allow for online voting — to changing the current primary and caucus schedule to diminish the influence of Iowa and New Hampshire – states whose populations are overwhelmingly white and economies far more rural than the rest of the nation.

But, people, rest assured, there are many, many proposals out there for reforming both the primary process and elections in general. These range from plan to make it easier to vote in primaries — including proposals to allow for online voting — to changing the current primary and caucus schedule to diminish the influence of Iowa and New Hampshire – states whose populations are overwhelmingly white and economies far more rural than the rest of the nation.

And then there’s campaign finance reform. Yikes! We better not go down that road right now.

So, keep some of this in mind as you observe and hopefully participate in the primary process in 2016. And don’t lose heart, citizens. If there’s one thing that history teaches us, it’s that while democracy is indeed a wondrous and virtuous system, it’s also messy and complicated. It always has been and always will be.

FURTHER READING

Geoffrey Cowan, Let the People Rule: Theodore Roosevelt and the Birth of the Presidential Primary (2016)

David W. Moore and Andrew E. Smith, The First Primary: New Hampshire’s Outsize Role in Presidential Nominations (2015)

Alan Ware, The American Direct Primary: Party Institutionalization and Transformation in the North (2002)