Back in the late nineteenth century Labor Day meant something more than a three-day weekend and the unofficial end of summer. This unique holiday was first celebrated on September 5, 1882. On that day thousands of workers in New York City risked getting fired for taking an unauthorized day off to participate in festivities honoring honest toil and the rights of labor. This first commemoration of Labor Day testified to labor’s rising power and unity in the Gilded Age and its sense that both were necessary to withstand the growing power of capital.

The Labor Day holiday originated with the Central Labor Union (CLU), a local labor federation formed in January 1882 to promote the interests of workers in the New York area. The CLU immediately became a formidable force, staging protest rallies, lobbying state legislators, and organizing strikes and boycotts. By August membership in the organization boomed to fifty-six unions representing 80,000 workers.

But CLU activists wanted to do more than simply increase membership and win strikes. They wanted to build worker solidarity in the face of jarring changes being wrought by the industrial revolution. Gilded Age workers were alarmed by the growing power of employers — from local building contractors to national corporations like Western Union — over their employees. With political leaders wedded to laissez faire economics, employers were free to increase hours, slash wages, and fire workers at will. Equally disconcerting was the growing gap between rich and poor, a disparity made shockingly clear by the emergence of millionaire industrialists and financiers with names like Gould, Stanford, Morgan, Rockefeller, and Carnegie.

These developments, noted labor leaders, called into question the future of the American republic. “Economical servitude degrades political liberties to a farce,” announced the CLU constitution. “Men who are bound to follow the dictates of factory lords, that they may earn a livelihood, are not free. … [A]s the power of combined and centralized capital increases, the political liberties of the toiling masses become more and more illusory.” CLU activists believed the establishment of a day celebrating the honest worker, the foundation of the republic, would open their eyes and compel them to reclaim their dissipating rights. As John Swinton, editor of the city’s only labor paper wrote, “Whatever enlarges labor’s sense of its power hastens the day of its emancipation.”

The precise identity of the CLU leader who in May 1882 first proposed the idea of establishing Labor Day remains a mystery. Some accounts say it was Peter “P. J.” McGuire, General Secretary of the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners (and future co-founder of the AFL), who proposed the idea. Others argue that it was another man with a similar last name, machinist Matthew Maguire. Official bragging rights to the title of “Father of Labor Day” aside, both men played key roles in promoting and organizing the original holiday.

After months of preparation the chosen day – Tuesday September 5, 1882 – finally arrived. Optimism among the organizers ran high, but no one knew how many workers would turn out. Few could expect their employers to grant them a day off and many feared getting fired and blacklisted for labor union activity. When William G. McCabe, the parade’s first Grand Marshall and popular member of Local No. 6 of the International Typographers Union, arrived an hour before the parade’s start, the situation looked grim. Only a few dozen workers stood milling about City Hall Park.

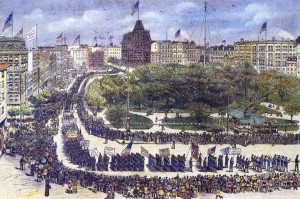

To the relief of McCabe and other organizers, some 400 men and a brass band had assembled by the time the parade touched off at 10:00 a.m. Initially, the small group of marchers faced ridicule from bystanders and interruptions in the line of march because policemen refused to stop traffic at intersections. As the parade continued north up Broadway, however, it swelled in size as union after union fell into line from side streets. Soon the jeers turned into cheers as the spectacle of labor solidarity grew more impressive.

Marchers held aloft signs that spoke both to their pride as workers and the fear that they were losing political power and economic standing in the republic:

To the Workers Should Belong All Wealth

Labor Built this Republic. Labor Shall Rule It

Less Work and More Pay

Strike with the Ballot

Don’t Smoke Cigars without the Union Label

Eight Hours for a Legal Day’s Work

Many wore their traditional work uniforms and aprons and walked behind wagons displaying their handiwork. Others dressed in their holiday best for the occasion.

Midway through the parade, the throng passed a reviewing stand at Union Square. Among the many dignitaries was Terence Powderly, Grand Master Workman of the Knights of Labor, the most powerful labor organization in the nation.

After moving up Fifth Avenue, past the opulent homes of Vanderbilt, Morgan, Gould and other recently-minted tycoons, the grand procession of 5,000 or more terminated at 42nd Street and Sixth Ave. There participants boarded elevated trains – extra cars had been added to handle the anticipated crowds – for a short ride to Wendel’s Elm Park at West 92nd Street for a massive picnic. Tickets for the event were just 25 cents and by late afternoon upwards of 25,000 workers and their families jammed the park to participate in the festivities and consume copious amounts of food and beer. Members of individual craft unions gathered under banners put up throughout the park. Several bands provided music, while speaker after speaker held forth from various stages and soapboxes.

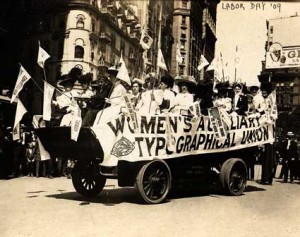

Thrilled with the success of their first effort, CLU leaders staged a second Labor Day the following year and drew an even larger number of participants. In 1884 the CLU officially designated the first Monday in September as the annual Labor Day, calling upon workers to “Leave your benches, leave your shops, join in the parade and attend the picnic. A day spent with us is not lost.” Upwards of 20,000 marched that year, including a contingent of African American workers (the first women marchers debuted in 1885).

With such an impressive start, the tradition of an annual Labor Day holiday quickly gained popularity across the country. By 1886 Labor Day had become a national event. Some 20,000 workers marched in Manhattan, and another 10,000 in Brooklyn, while 25,000 turned out in Chicago, 15,000 in Boston, 5,000 in Buffalo, and 4,000 in Washington, D.C. Politicians took notice and in 1887 five states, including New York, passed laws making Labor Day a state holiday. Seven years later – just a dozen years after the first celebration in New York — President Grover Cleveland signed into law a measure establishing Labor Day as a holiday for all federal workers.

Labor Day caught on so quickly among Gilded Age workers because unlike the traditional forms of labor activism (i.e., striking and picketing) or civic holidays commemorating victories in war, it drew together workers for the purposes of celebration. As P. J. McGuire later wrote of the parade,

No festival of martial glory of warrior’s renown is this; no pageant pomp of warlike conquest … attend this day. … It is dedicated to Peace, Civilization and the triumphs of Industry. It is a demonstration of fraternity and the harbinger of a better age – a more chivalrous time, when labor shall be best honored and well rewarded.

In the twentieth century, Labor Day parades grew into massive spectacles of pride and power. The highpoint came 1961 when 200,000 workers processed up Fifth Avenue behind Grand Marshall Mayor Robert Wagner, passing on the reviewing stand dignitaries that included Governor Nelson Rockefeller, Senator Jacob K. Javitts, and former President Harry S. Truman. But the strength of organized labor demonstrated by that parade –union membership had just reached its historic highpoint with 39% of the American workforce – was already being eroded by the emergence of the service economy, globalization, and a political climate often hostile to unions. By the late 1990s fewer than fifteen percent of American workers belonged to unions and Labor Day parades disappeared in many cities. Or, as is the case in New York City, parades were moved to the weekend following Labor Day so as to avoid competing with the public’s desire for a final three-day weekend of recreation.

Still, it would be unwise to predict the Labor Day’s demotion to the status of Arbor Day or Flag Day. Despite the fact that few Americans are even remotely aware of the struggle and spirit that laid the foundation of their current prosperity, comfort, and leisure, many of the issues that inspired the first Labor Day persist. Public distrust of corporations has spiked in recent years as the result of scandals in accounting, campaign finance, and massive payouts to departing executives. All the while, polls indicate that more and more Americans are worried about job security, health care costs, and pension funding. Other workplace issues such as sexual harassment, discrimination, and family leave continue to attract attention. Whether these concerns ultimately lead Americans to “Strike with the Ballot” remains to be seen. In the meantime Labor Day will endure for the foreseeable future as an annual reminder of battles won and battles yet to be joined.

Still, it would be unwise to predict the Labor Day’s demotion to the status of Arbor Day or Flag Day. Despite the fact that few Americans are even remotely aware of the struggle and spirit that laid the foundation of their current prosperity, comfort, and leisure, many of the issues that inspired the first Labor Day persist. Public distrust of corporations has spiked in recent years as the result of scandals in accounting, campaign finance, and massive payouts to departing executives. All the while, polls indicate that more and more Americans are worried about job security, health care costs, and pension funding. Other workplace issues such as sexual harassment, discrimination, and family leave continue to attract attention. Whether these concerns ultimately lead Americans to “Strike with the Ballot” remains to be seen. In the meantime Labor Day will endure for the foreseeable future as an annual reminder of battles won and battles yet to be joined.