InThePastLane.com by Edward T. O’Donnell

The story of the Statue of Liberty provides an excellent opportunity to examine how the icons and traditions a society holds dear often originated with very different purposes and meanings. Put another way, it allows us to ponder yet another example of one of my rules of history—namely, that nothing “has always been.” It was not until decades after 1776 that Americans began to consider the Declaration of Independence a sacred document. Thanksgiving only became a major national holiday after the Civil War. Freedom of speech, despite its enshrinement in the Bill of Rights, only acquired its broad definition in the early 20th century. And the Statue of Liberty, long a symbol of America’s revered tradition of welcoming the world’s “huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” originally had nothing to do with immigration. That association developed in the mid-20th century, some fifty years after its grand coming out party in 1886.

The story of the Statue of Liberty provides an excellent opportunity to examine how the icons and traditions a society holds dear often originated with very different purposes and meanings. Put another way, it allows us to ponder yet another example of one of my rules of history—namely, that nothing “has always been.” It was not until decades after 1776 that Americans began to consider the Declaration of Independence a sacred document. Thanksgiving only became a major national holiday after the Civil War. Freedom of speech, despite its enshrinement in the Bill of Rights, only acquired its broad definition in the early 20th century. And the Statue of Liberty, long a symbol of America’s revered tradition of welcoming the world’s “huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” originally had nothing to do with immigration. That association developed in the mid-20th century, some fifty years after its grand coming out party in 1886.

To raise funds for the pedestal on which the Statue of Liberty would stand, the arm and torch were sent to America in 1876 for display at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition.

So what did the Statue of Liberty stand for in 1886? The answer is found in its origins as a gift of the French people to celebrate republican government as established in the American and French Revolutions. The brief version of the story is as follows. A French legal scholar, political leader, reformer, and abolitionist Edouard Rene de Laboulaye proposed in 1865 (some accounts say 1870) the idea of the French people funding the creation of a monument to American independence to mark the centennial of the American Revolution in 1876. Laboulaye hoped the monument would strengthen ties between France and the U.S. and inspire his fellow French reformers to restore republican liberties being suppressed under the rule of Napoleon III. Laboulaye eventually secured the services of sculptor Frederic Bartholdi who, after years of delays, eventually commenced work on the Statue in 1875. The Statue’s arm and torch arrived one year later to be displayed at the Philadelphia world’s fair. As the rest of the Statue arrived in crates by 1883, Americans raised the money for the pedestal on Bedloe’s Island in New York Harbor. By the fall of 1886, as the Statue neared completion, officials planned a massive celebration to accompany the unveiling.

Lady Liberty holds a tablet with the inscription, July 4, 1776, to commemorate the birth of the American republic.

That the Statue had everything to do with celebrating republican ideals and nothing to do with immigration is further demonstrated by the full name assigned it—“Liberty Enlightening the World”—and its symbolism. Lady Liberty carries in her right hand the torch of liberty and in her left a tablet inscribed with July 4, 1776. Moreover, she faces the Atlantic Ocean and Europe. Her message is clear: Hey, Europe and the rest of the world—you want some of this American peace, prosperity, and progress? Well, then rid yourself of monarchs, aristocracies, established churches, and fixed classes and embrace republican government.

That was the central message at the gigantic civic celebration that attended the Statue’s unveiling on October 28, 1886. More than a million people gathered in New York City for the festivities (which, incidentally, included the first ticker-tape parade), including President Grover Cleveland, members of Congress, representatives of the French government, and other foreign dignitaries. The theme of this grand civic celebration and the many speeches and editorials that marked it was a celebration of the American republic and the belief that it stood as an inspiring example to the rest of the world. “We will not forget that Liberty has here made her home,” declared President Cleveland in his speech. Its radiant light, symbolized in the Statue’s torch, would radiate outward to penetrate the “darkness of ignorance and man’s oppression until Liberty enlightens the world!” The only reference to immigrants was a negative one from railroad magnate Chauncey Depew, who declared republican self-government and not “Anarchists and bombs” as the best remedy for the social unrest then rocking the nation (1886 was the year of a record number of strikes and the Haymarket bombing), unrest many associated with radical immigrants spreading dangerous ideologies like socialism and anarchism.

If the Statue of Liberty originated without any consideration of immigration, then what about the poem, “The New Colossus” that is so closely associated with it?

With silent lips. “Give me your

tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses

yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your

teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless,

tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the

golden door!”

Emma Lazarus, a Jewish-American poet, wrote “The New Colossus” in 1883. But it would be 50 years before it garnered attention for its message connecting the Statue of Liberty to the theme of welcoming immigrants.

Written in 1883 by Emma Lazarus, it clearly celebrated the Statue as a beacon of hope to immigrants seeking freedom. But the historical record shows that this idea began and ended with Lazarus. No one paid any attention to the poem. Three years later, no one mentioned it at the unveiling ceremony. None of Lazarus’ obituaries or eulogies mentioned in when she died in 1887. Even when a wealthy New Yorker in 1903 paid for a bronze tablet bearing the poem to be attached to the base of the Statue (more as a tribute to Lazarus than a celebration of immigration), it drew almost no attention. As late as the 1930s the information provided by the National Park Service (which managed the Statue) told visitors to the Statue that it was a symbol of Franco-American unity and republican liberty.

Of course, that was the official interpretation. The millions of immigrants who entered New York harbor after the Statue of Liberty was unveiled in 1886 interpreted it as a beacon of hope and symbol of freedom from Old World oppression. Native-born Americans in this period harbored no such warm and fuzzy feelings. The period 1870-1920 witnessed a surge in anti-immigrant sentiment that eventually resulted in immigration restriction in 1924.

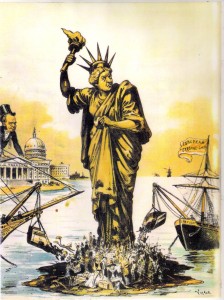

“Dumping European Garbage” (Judge magazine, 1890) was typical of the nativist cartoons ca. 1880-1920 that used the image of Lady Liberty to condemn immigration.

Most Americans in this period looked upon the “huddled masses” as a threat to American society, not the building blocks of a vibrant and prosperous multi-ethnic democracy. Indeed, the most common use of the Statue of Liberty image was to condemn immigration.

So, when did the more familiar interpretation of the Statue take hold? Tellingly, it wasn’t until after Congress sharply restricted immigration in 1924 that Americans began to assign a new meaning to the Statue—that of a goddess of liberty welcoming the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free” (yes, it’s in the 1930s when Lazarus’ poem becomes popular). While this might seem strange, history tells us that it’s actually quite common. Societies often begin honoring something only after it’s gone. Americans despised Native Americans until they were defeated and confined to reservations in the 1880s. Then Americans embraced a romanticized image of Native Americans that remains powerful to this very day.

These days, this image dominates the official US government website providing information to new immigrants about citizenship.

In the case of the Statue of Liberty, writes historian John Higham, “So long as millions of immigrants entered ‘the golden door,’ the Statue of Liberty was unresponsive to them; it served other purposes. After the immigrant ships no longer passed under the New Colossus in significant numbers, it enshrined the immigrant experience as a transcendental national memory. Because few Americans were now immigrants, all could think of them as having been immigrants.” By the 1950s a Museum of Immigration opened at the Statue and record-breaking crowds arrived to tour it. And so it was that the Statue of Liberty, notes Higham, “gradually joined the covered wagon as a symbol of the migrations that had made America.”

Like I always say: nothing “has always been.”

Follow me on Twitter @InThePastLane

Sources and Further Reading:

James B. Bell and Richard I. Abrams, In Search of Liberty: The Story of the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island (Doubleday, 1984).

Edward Berenson, The Statue of Liberty: A Transatlantic Story (Yale, 2012).

John Higham, “The Transformation of the Statue of Liberty,” in John Higham, Send These to Me: Immigrants in Urban America (Johns Hopkins, 1984).

Yasmin Sabina Khan, Enlightening the World: The Creation of the Statue of Liberty (Cornell, 2010).

The New York Times, October 28, 1886.