The song “White Christmas” was recorded in May 1942 and debuted in August as a song in the film, “Holiday Inn”

“White Christmas,” the song that first topped the charts in early December 1942, was a war song? It’s true—not in its lyrics of days that are “merry and bright,” of course, but in terms of the context that launched it to an exalted status in the annals of pop music history. In fact, the connection between “White Christmas” and World War II is but one of several surprising details related to the song’s origins.

Like the fact that it was written by a Jewish songwriter (as was the case with many American Christmas songs, including “Rudolph” and “Chestnuts Roasting on an Open Fire”). “White Christmas” was written by Irving Berlin. Born Israel Baline in Siberia in 1888, he arrived in America with his family in 1893. They settled on New York’s Lower East Side, at the time the largest Jewish enclave in the world. But not everyone in the neighborhood was Jewish. There was an Irish family living in their building and they took a liking to the young “Izzy” and often invited him into their apartment. Thus it was in December 1893 that he witnessed his first Christmas in America—a warm a delightful experience he never forgot. Later as an adult, he married an Irish Catholic woman named Ellin Mackay. Because they raised their children as Christians, Berlin learned to love the holiday (albeit, its secular trappings) all the more.

In classic American fashion, Russian Jewish immigrant Irving Berlin wrote “White Christmas,” the most popular Christmas song of all time

Years later in January 1940, in the days following a happy Christmas holiday with his family, the now quite famous Irving Berlin penned, “White Christmas.” He sat on the song for more than a year, unsure of what to do with it, until approached by a Hollywood studio to write the score for “Holiday Inn,” a film that featured songs about each of the major holidays. Bing Crosby had been selected to play the lead and sing most of the songs. When he heard “White Christmas” for the first time, he assured Berlin that he’d written a gem.

By the time of the filming of “Holiday Inn,” Crosby was the most famous singer in America, perhaps the world. His manly, yet emotive crooning was unlike anything that preceded it in the world of pop music. This was due in part to Crosby’s extraordinary voice, but also to his technique. He was the first singer to embrace and then master the microphone, a new medium for broadcasting and recording introduced in the 1920s. Historians of pop music invariably speak of Crosby’s uncanny “caressing” of the microphone with his voice, creating an unparalleled intimacy and connection with his listeners.

Crosby recorded “White Christmas” in the decidedly non-Yuletide season of May 1942. “Holiday Inn” opened in August and became an instant hit at the box office. So, too, was its centerpiece song, “White Christmas” (the only one sung twice in the film). It hit the Top 30 charts on October 3 and kept right on marching upward until it hit #1 on October 31, a position it held for an unprecedented eleven weeks. Decca, the label that produced the record, was swamped with orders and barely kept up with demand.

Crosby recorded “White Christmas” in the decidedly non-Yuletide season of May 1942. “Holiday Inn” opened in August and became an instant hit at the box office. So, too, was its centerpiece song, “White Christmas” (the only one sung twice in the film). It hit the Top 30 charts on October 3 and kept right on marching upward until it hit #1 on October 31, a position it held for an unprecedented eleven weeks. Decca, the label that produced the record, was swamped with orders and barely kept up with demand.

Berlin’s skill as a songwriter and Crosby’s talent as a singer had combined to produce an American classic. But there was one additional factor that helps explain the phenomenal success of “White Christmas”—timing. As Jody Rosen writes in his book, White Christmas: The Story of an American Song, the fall of 1942 was the first holiday season away from home for millions of American servicemen. Demand by American GI’s for “White Christmas” records exploded in September – fully three months before the holiday. The reason is clear: the song stoked their longing to be home with their families. “In the song’s melancholic yearning for Christmases past,” writes Rosen, “listeners heard the expression of their own nostalgia for peacetime.” Indeed, in a way that astonished Berlin and nearly everyone else, this song of peace and love soon became a most unlikely war anthem. Unlike George M. Cohan’s World War I call to arms, “Over There!”, “White Christmas” did not appeal to the martial spirit or vengeance. Rather, it reminded Americans on both the frontline and homefront what was at stake in the war. “When Irving Berlin set 120,000,000 people dreaming of a White Christmas,” opined the Buffalo Courier-Express, “he provided a forcible reminder that we are fighting for the right to dream and memories to dream about.” When Crosby visited the troops in Europe in late 1944, his rendition of “White Christmas” brought tears to the eyes of the most battle-hardened soldiers.

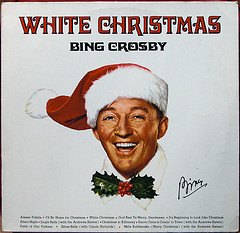

For the next five years the Crosby-Berlin classic surged to the top of the charts each Christmastime, hitting #1 in 1945 and 1947. All told, it made the Top 30 sixteen times in the three decades that followed its release. The song’s popularity and staying power proved irresistible to Hollywood executives who in 1954 released the hit feature film “White Christmas” starring Crosby and Danny Kaye.

Long after the film disappeared, “White Christmas” kept going, Crosby’s recording sold more than 30 million copies – more than any other pop song in history. Dozens of singers, from Loretta Lynn to Destiny’s Child have recorded versions of the song, pushing total worldwide sales past 160 million – and counting.

None, of course, compare to the original as sung by Crosby in 1942, a song of peace, love, and fond memories of times “merry and bright” that arrived just when the nation needed it.

One last thought to consider: the U.S. has had many of wars since 1945 and each has generated its share of popular songs. But none of them conjure up warm and fuzzy feelings like “White Christmas.” Indeed, some of the most popular were anthems that protested war—think Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” during Vietnam. The reason is simple: World War II was the last war in U.S. history to begin and end with overwhelming popular support.

Follow me on Twitter @InThePastLane

Sources and Further Reading:

Ace Collins, Stories Behind the Best-Loved Songs of Christmas (Zondervan, 2001)

Edward Jablonski, Irving Berlin: American Troubadour (Holt, 1999)

Penne L. Restad, Christmas in America: A History (Oxford, 1996)

Jody Rosen, White Christmas: The Story of an American Song (Scribner, 2007)