InThePastLane.com By Edward T. O’Donnell

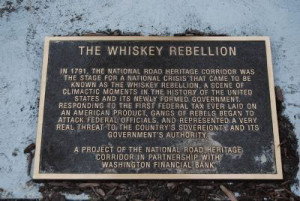

On August 7, 1794 President George Washington decided the time had come for action. Popular protest by farmers in western Pennsylvania against a new federal excise tax on whiskey had recently turned into an armed insurrection. Recognizing the threat this “Whiskey Rebellion” posed to the new constitutional government established only a few years earlier, Washington mobilized a force of federal soldiers and personally led them to confront the rebels.

The men and women who settled on the colonial frontier in the 17th and 18th centuries were in many ways the ultimate risk takers. They were also more often than not poor. With the best land near the coastal cities and waterways (vital to transporting agricultural produce) taken by earlier arrivals and the wealthy, those who wanted to own land headed for the interior where both opportunity and peril (in the form of hostile Indians, economic isolation, and lawlessness) abounded. Colonial governments welcomed these risk takers because they expanded the line of settlement westward and acted as a buffer against Indian attacks. But these same officials were also leery of the colonial frontiersmen’s fiercely guarded independence and resistance to government authority—especially taxes. Colonial history includes many episodes of rebellion by discontented frontier settlers, including Bacon’s Rebellion (1676), the Paxton Boys (1763), and the Regulators (1760s).

So the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794 fits into a larger tradition of frontier discontent in early American history. But why all the fuss about a tax on whiskey?

The answer lies with the important role that whiskey played in frontier society. Whiskey became a vital part of everyday frontier life, perhaps because it was so tough, lonely, and devoid of diversion. Many family farms maintained a still for producing whiskey and the average adult male on the frontier consumed prodigious amounts of the stuff each year. Observers of frontier gatherings such as weddings and harvest festivals were often shocked by the amount of whiskey consumed and the violent games and wrestling matches that followed. This explains why easterners generally viewed frontier inhabitants as backward, violent, and crude.

But whiskey also played an essential role in the local economy as a form of currency. This was especially true when it came to obtaining important goods from frontier market towns like Pittsburgh. Primitive roads and difficult terrain on the frontier made it prohibitively expensive to transport heavy barrels of grain to market. But a farmer could distill one hundred pounds of grain into one gallon of whiskey that weighed a little more than eight pounds and fetched a price of 25 cents in Lancaster or Pittsburgh. That money allowed a family to purchase necessities like tools and guns, as well as a few luxuries such as coffee and sugar.

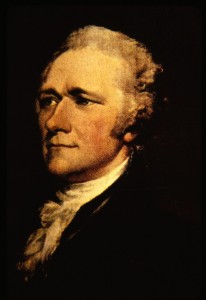

Given how central it was to his everyday life and livelihood, the typical frontier farmer reacted angrily to any perceived threat to his whiskey. Imagine, then, his reaction to the news in 1791 that the new federal government had, at the behest of the Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, enacted a new excise tax on whiskey. Similar taxes on liquor had been on the books since the 1690s, but they applied only to rum. The 1791 tax on whiskey (seven cents per gallon) was intended to raise much needed revenue for the federal government to pay off its huge debt (much of it being state debts run up during the Revolution). It also contained a provision that taxed large distillers at a lower rate, putting a greater burden on the small-scale distillers.

Outraged, frontier farmers took a page from the Revolutionary era and like their patriotic brethren during the Stamp Act crisis of 1765-66, formed a resistance movement. From Pennsylvania to Georgia, distillers refused to register their stills with their local country tax office. Farmers charged with failure to pay the whiskey tax refused to travel to Philadelphia to stand trial. And federal revenue collectors who ventured to the frontier were beaten, tarred and feathered, and otherwise harassed to the point where they feared for their lives.

Washington and Hamilton initially opted for a wait and see approach, hoping the resistance would died down. But from 1791 when the tax took effect, to the summer of 1794, defiance only grew stronger and President George Washington was concerned for the future of the country.

Protests and attacks on tax collectors occurred all across the frontier, but the most intense spirit of rebellion was found in Pennsylvania. One particularly notable incident involved farmer and distiller William Miller. In mid-July 1794, he was served a summons by a local politician named John Neville to appear before a judge in Philadelphia to answer charges of tax evasion. Miller refused and sent Neville packing. “I felt my blood boil,” he later recounted.

Neville returned to his large manor home and soon found it surrounded by a force of 50 armed men. He and his family and slaves managed to drive them off, killing one of the rebel farmers. Neville then asked for military protection and received a contingent of 12 soldiers under the command of Major Abraham Kirkpatrick from a fort near Pittsburgh. The next morning a larger rebel force arrived under the command of Major James McFarlane, a local farmer and Revolutionary War veteran. In the ensuing fight, McFarlane was shot and killed — some say after he was lured toward Neville’s house by a flag of surrender. The rebels then stormed the house and forced the surrender of Kirkpatrick and his soldiers (they were released on condition that they leave the area). Finding that Neville had escaped earlier, the rebels then burned his house and outbuildings.

Thousands turned out for the funeral of Major McFarlane and it soon turned into a giant recruiting rally for the rebel farmer cause. Within weeks a large rebel force of some 5,000 to 7,000 had gathered near Pittsburgh and begun to drill. On Aug. 1 a contingent marched to Pittsburgh, where they were met by a nervous reception committee eager to avoid any violence. They plied the rebels with food and whiskey and agreed to banish certain citizens of questionable loyalty.

While this maneuver seemed innocent enough, the prospect of Pittsburgh being overrun and occupied by a larger rebel force terrified the Washington administration. Clearly, if the new federal government was to have any credibility, Washington and his treasury secretary, Alexander Hamilton, would have to make a stand. On Aug. 7, 1794 Washington issued a proclamation, requisitioning 13,000 militiamen from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, and Virginia and ordering the frontier rebels to return to their homes. Federal and state commissioners were sent to the frontier with offers of amnesty to all who would quit the rebellion. When they received a weak response to this overture, the decision was made to send the army to the frontier.

Commanded by Revolutionary War hero and current governor of Virginia Henry “Lighthorse Harry” Lee, the force contained many other notables, including five of Washington’s nephews, two other state governors, and a young soldier named Meriwether Lewis (of future Lewis and Clark fame). Gathering near Harrisburg in October 1794, they were reviewed by President Washington, who arrived to boost their spirits and to remind them of their loyalty to the federal government.

All was in order except for one thing: the rebellion had begun to fizzle in the face of the federal threat. Most rebel farmers slipped away and returned to their farms and stills. With no rebel army to disperse, Hamilton ordered the militia to fan out and arrest any suspected ringleaders. Hundreds were taken and questioned and eventually 20 were sent to Philadelphia for prosecution. They were paraded through the streets with “Insurrection” inscribed on their hats and thrown in jail to await trial. Two were eventually convicted of treason and sentenced to hang. But Washington decided that leniency was in order and pardoned both men.

Hamilton likewise played a role in defusing the crisis by having his tax collectors also act as purchasing agents for the federal army. Now the despised collectors became customers who purchased at top dollar vast quantities of whiskey to satisfy the weekly ration owed each soldier. The hated excise tax was repealed a few years later during the presidency of Thomas Jefferson.

Although comical in some respects, the Whiskey Rebellion of 1791-94 represented the first great challenge to the new federal government established under the Constitution in 1788. Washington’s forceful response legitimized federal authority and went a long way toward securing future generations of stable government. And the frontier farmers who led the revolt learned to channel their anger into politics as a more effective way to get the justice they sought.

Sources and Further Reading:

William Hogeland, The Whiskey Rebellion: George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and the Frontier Rebels Who Challenged America’s Newfound Sovereignty (2006)

Thomas P. Slaughter, The Whiskey Rebellion: Frontier Epilogue to the American Revolution (1988)