InThePastLane.com By Edward T. O’Donnell

On August 17, 1877, young William Henry McCarty became a killer and outlaw. Attacked by a barroom bully in Arizona, the seventeen-year old killed the man with his pistol and fled to nearby New Mexico where he tried to start a new life as a ranch hand. But he would soon find himself embroiled in a bitter and bloody rancher feud, a conflict that propelled him to national infamy as “Billy the Kid,” one of the most notorious outlaws in the west.

Billy the Kid was born William Henry McCarty to Irish immigrant parents Catherine and Michael McCarty in New York City on September 17, 1859. Like many of their fellow Irish immigrants, the McCarty’s lived in poverty in a run down tenement on the Lower East Side. When Billy’s father died soon after his birth, he and his mother headed west, eventually landing in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

There in 1873 Billy’s mother married a miner named William Antrim. Her death the next year from a long bout with tuberculosis hit Billy hard and set him on a downward spiral. He accompanied his step-father to a silver strike in Arizona, near a place called Globe City. Antrim alternated between abusing and ignoring Billy, leaving him to fall in with a rough crowd in the mining town. By age sixteen, Billy was known as a violent and reckless young man who possessed little regard for authority. Shortly after his arrest for stealing laundry, he set out on his own, supporting himself as a ranch hand, cattle rustler, and gambler.

Up to this point the 17-year old’s offenses were relatively minor, given the rough and lawless character of life in the 1870s southwest. But that changed one afternoon in August 1877 when Billy got into an altercation with a fellow rowdy named Frank Cahill. “Windy” Cahill was a big man – considerably larger than the slight Billy – who delighted in taunting others. No one remembers what Billy said in response to one of the burly man’s barbs, but it prompted Cahill to attack. He threw Billy to the ground and began to pummel him. Somehow Billy managed to pull his gun and fired into Cahill’s stomach. When Cahill died the next day, Billy was long gone.

Now an outlaw, he headed for New Mexico and again fell in with cattle rustlers and horse thieves. But as was common in the wilder days of the west, men like Billy were often hired by ranchers (sometimes the very ones they stole from) to protect their herds from other rustlers or rival ranchers imposing on their grazing and watering areas. Billy was hired by a wealthy rancher named John Henry Tunstall, a man then embroiled in a bitter struggle with a rival rancher named James Dolan. Dolan and his partner William Murphy held a monopoly on the local beef market in Lincoln County and were notorious for paying prices for beef that kept ranchers on the verge of ruin. When Tunstall, the largest rancher in the county set out to break the monopoly, he found that Dolan controlled all the local politicians, judges, and businessmen. Worse, Dolan hired rustlers to harm Tunstall’s cattle and drive him out of business. Tunstall’s response was to hire his own men, including Billy.

The simmering feud between Dolan and Tunstall erupted into a conflict that came to be called the Lincoln County War when Dolan had his men assassinate Tunstall on April 18, 1878. When the local sheriff, a man under the thumb of Dolan, refused to arrest any suspects, Billy and a group of Tunstall’s men took matters into their own hands. Only days after the assassination, they hunted down and killed two of the suspects. Three weeks later they killed Brady in an ambush. Another suspect was shot soon thereafter. Dolan’s men got revenge a few weeks later when they gunned down three men in Billy’s group and Tunstall’s business partner. Billy narrowly escaped.

The Lincoln County War cooled after that episode. Billy laid low in Fort Sumner, New Mexico (not far from Lincoln) until arrested by a posse sent by the governor of the New Mexico territory. Billy soon escaped and rejoined his friends in the hills near Fort Sumner. In late December 1880 Sheriff Pat Garrett found them and arrested Billy, charging him with the murder of Sheriff Barry. A jury found Billy guilty and sentenced him to hang, but he again escaped the day before going to the gallows, killing both his guards in the process.

By now Billy’s exploits had become the stuff of sensational stories in newspapers across the country. Journalists often exaggerated the details and weaved in copious amounts of fiction into their dispatches, turning Billy – a nondescript ranch hand caught in the midst of a brutal range war – the nation’s most famous outlaw. And for good measure, they gave him a catchy nickname, “Billy the Kid,” a moniker that derived from Billy’s youth (he was only 21) and boyish face.

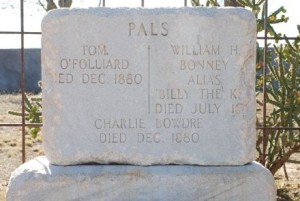

The tombstone marking the grave of Billy the Kid in Fort Sumner, NM. The original stone was stolen and this one was placed here in 1930.

Sheriff Garrett eventually caught up with Billy on July 14, 1881 and killed him with a bullet in the heart. Garrett was heralded for ridding the west, in the words of the New York Times, of “probably the most noted desperado on the Pacific coast … [and] one of the most dangerous characters this country has produced.” That hyperbole indicated the myth making yet to come as novels, ballads, movies, and oral tradition turned William Henry McCarty into a national icon.

Sources and Further Reading:

Mark Lee Gardner, To Hell on a Fast Horse: Billy the Kid, Pat Garrett, and the Epic Chase to Justice in the Old West (2010)

Pat F. Garrett, The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid (1882)

Michael Wallis, Billy the Kid: The Endless Ride (2007)