[Please note: this piece originally appeared in the Huffington Post, September 23, 2015]

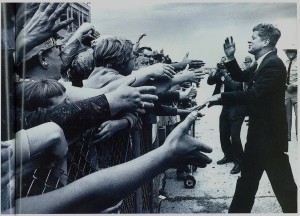

When Pope Francis arrives in the United States this week, he will be greeted with an extraordinary outpouring of affection and adulation. It will come not merely from Catholics, but also from among Americans of all faith traditions and even non-believers. The sources of this favorable view of Pope Francis vary, from progressive Catholics hoping for change in the Church on issues like abortion and gay rights, to Americans thrilled to see the pontiff speak so powerfully on wealth inequality and threats to the environment. Francis’s popularity has earned him a visit to the White House and an opportunity to speak before a joint session of the U.S. Congress.

St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City stood as the most vivid symbol of the Catholic arrival in the U.S.

But it was not that long ago that word of the impending arrival of a pope on the shores of the United States would have triggered bloody riots and a call to arms. Indeed, for most of this nation’s history Americans saw the Pope as a sinister and dangerous leader who was determined to destroy America’s experiment in republican government.

Anti-Catholicism has deep roots in American history. But its hey day was the mid-nineteenth century. What sparked this surge in anti-Catholic hostility was the arrival of several million Catholic immigrants from Europe (primarily Ireland, Germany, and later Italy). Its impact was dramatic and unnerving for Americans who considered the United States a Protestant country. In New York City, for example, the Catholic population boomed from just ten percent of the total in 1815 to fifty percent in 1865.

Why did Protestant Americans fear and despise Catholicism so intensely? Some opposition stemmed from differences in religious doctrine on matters like baptism and the Trinity. But most focused on broader social and political questions. First, opponents of Catholicism argued that Catholics could never become good republican citizens because they owed allegiance to a foreign potentate – the Pope – rather than popularly elected leaders.

Second, Protestants pointed to the fact that the Pope and his Church had a long record of hostility towards the fruits of the Enlightenment, everything from science (e. g. the persecution of Galileo) to individualism, reason, and secularism. And the Church had condemned democracy and upheld monarchy and obedience to traditional authority.

This image, “Popery Undermining Free Schools and Other American Institutions,” appeared in Edward Beecher’s 1855 book, The Papal Conspiracy Exposed and Protestantism Vindicated. It shows a kingly pope pointing at an American public school, indicating his intention to begin his overthrow of the republic here.

Third, these first two points formed the foundation of a far greater threat posed by the Catholic Church: the Pope was secretly plotting to destroy the young American republic. Such a claim sounds absurd to modern Americans, but in the mid-nineteenth century it held widespread credence. Indeed, one of the best-selling genres of literature in this period were books purporting to reveal the papal plot to overthrow America. Many were written by well-known and respected figures such as Samuel F. B. Morse of telegraph fame and Edward Beecher, brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe. Morse, for example warned in a popular work, The Foreign Conspiracy against the Liberties of the United States (New York, 1835), that “Popery is a political, a despotic system, which must be resisted by all true patriots… We may sleep, but the enemy is awake; he is straining every nerve to possess himself of our fair land. We must awake, or we are lost.” His was one of hundreds of anti-Catholic books and pamphlets published between 1820 and 1860, not to mention many newspapers and magazines with titles like, The Protestant Vindicator.

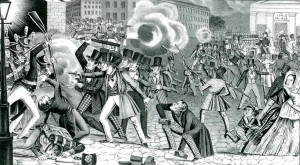

The 1844 “Bible Riots” in Philadelphia was the worst incident of anti-Catholic violence in this period. The dispute centered over whether Catholic children in public schools could read from Catholic bibles rather than Protestant ones.

In the midst of this fury highly organized political movements such as the Know Nothings emerged to mobilize against a perceived Catholic invasion of America. “Every Catholic stands committed as an enemy to the Republic,” declared one Know Nothing newspaper. “Let us regard every Roman Catholic as an enemy to the country—and so treat him.” This attitude led to countless episodes of anti-Catholic violence, the most infamous being the 1844 Bible Riots in Philadelphia that left 20 dead and 3 Catholic churches in ashes.

Anti-Catholicism and anti-popery in the United States persisted for decades beyond the 1850s. But it gradually diminished as Catholic immigrants assimilated into American life and became contributing members of society. It also helped, of course, that the feared papal plot to destroy America never materialized. After World War II some still questioned whether Catholics could be good Americans. But John F. Kennedy’s election in 1960 effectively put an end to that issue (at least in mainstream American politics). Today, Catholics make up a third of the members of Congress and six of nine justices on the Supreme Court. So Pope Francis need not fear that his visit will revive the Know Nothings.

Polls show that many Americans fear an Islamic conspiracy to take over America. Many 19th century Americans feared a similar Catholic conspiracy.

This reality is a testament to the strength of religious tolerance in modern American society. But we must not delude ourselves into thinking our work is done on this front. For the history of United States makes clear that this tradition of religious tolerance is one that has evolved and expanded over time to include many faiths initially deemed beyond the pale, including not just Catholics but also Jews, Mormons, and Jehovah’s Witnesses. We would do well to keep this in mind as recent immigration continues to expand the nation’s religious diversity. This is especially true in the case is Islam, a religious tradition that polling data reveals many Americans view with fear and hostility not very different from that reserved for Catholics a few generations ago.