Voting in modern America is done privately, but this practice became widespread only in the early 20th century.

This month, when Americans head to the polls to elect men and women to public offices, they will cast their ballots in secret, beyond the watchful eyes of their fellow citizens. Few Americans would have it any other way. We are accustomed to think of voting as a very private matter, akin to a visit to the doctor. And yet the truth is that secret balloting is a relatively recent innovation in American democracy. Most Americans would be shocked to know that it was only in the early 20th century that the nation began adopting a secret ballot.

The earliest voting in colonial America did not even involve a ballot. The most common form of voting was by show of hands or viva voce (voice vote). Historian Charles S. Sydnor in his book, Gentlemen Freeholders: Political Practices in Washington’s Virginia, describes a typical election day scene in mid-eighteenth century Virginia:

As each freeholder came before the sheriff, his name was called out in a loud voice, and the sheriff inquired how he would vote. The freeholder replied by giving the name of his preference. The appropriate clerk then wrote down the voter’s name, the sheriff announced it as enrolled, and often the candidate for whom he had voted arose, bowed, and publicly thanked him.

This practice of public voting lasted in many communities well into the early nineteenth century.

Two considerations explain the popularity of viva voce and show-of-hands voting. First, it made practical sense. Because voting was restricted to a relatively small number of people—white male property owners—there was no need for an elaborate system of balloting. Second, Americans considered public voting a virtue and a necessity. To use a familiar modern term, the nation’s early practitioners of democracy valued transparency. Public voting diminished the possibility that corrupt officials might manipulate the final tally. It also reflected the widely revered republican ideal of virtue. True citizens of a republic pursued virtue, not personal or party interests, in the political realm. A virtuous voter, therefore, had nothing to fear by making his vote known to all.

Two considerations explain the popularity of viva voce and show-of-hands voting. First, it made practical sense. Because voting was restricted to a relatively small number of people—white male property owners—there was no need for an elaborate system of balloting. Second, Americans considered public voting a virtue and a necessity. To use a familiar modern term, the nation’s early practitioners of democracy valued transparency. Public voting diminished the possibility that corrupt officials might manipulate the final tally. It also reflected the widely revered republican ideal of virtue. True citizens of a republic pursued virtue, not personal or party interests, in the political realm. A virtuous voter, therefore, had nothing to fear by making his vote known to all.

George Caleb Bingham’s painting, “Country Election” (1852), depicts the electoral process as not only public, but also chaotic, corrupt, and drunken.

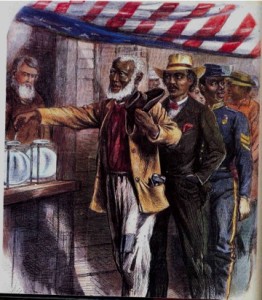

Voting remained public and transparent in the nineteenth century even as more and more communities began to use paper ballots. The turn to paper ballots was made necessary by population growth (especially in cities) and the elimination of property requirements for voting that opened up voting to nearly all while males by 1830. This accompanying painting by George Caleb Bingham, however, makes it clear that paper balloting was anything but private. In Bingham’s 1852 scene a voter, having made his way through a gauntlet of men trying to influence his vote, hands his ballot to a public official. But who he voted for is plain for all to see because the ballot he turned in had been handed to him moments earlier by a candidate or party operative (if you look closely, you will notice that the man behind him wearing the top hat is handing out ballots). Often these ballots were distinguished from one another by color, making it extremely easy to see how a person voted. Official ballots printed and distributed by the government only became the norm in the early 20th century—at the very same time and for the very same reasons that secret balloting took hold.

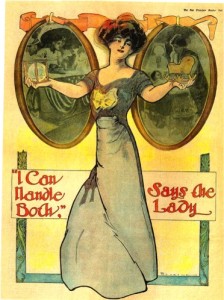

The popular glass globe “ballot box,” along with colored ballots, ensured that voting remained a very public affair in the nineteenth century.

Just how transparent voting was in the nineteenth century is exemplified in the wide adoption of the glass globe “ballot box” in the second half of the nineteenth century. So popular was this glass ballot box, it was used by political cartoonists as a symbol of democracy. Note its inclusion in many Thomas Nast cartoons published in Harper’s Weekly in the 1860s and 1870s (see gallery of images at the end of this article).

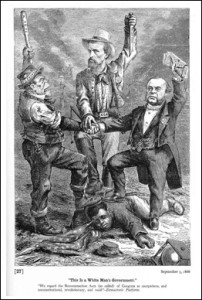

Political cartoonist Thomas Nast was a reformer who despised Boss Tweed and Tammany Hall for their corrupt political practices.

This Nast cartoon depicting William “Boss” Tweed explains why Americans eventually rejected public voting in favor of secret voting, or what the reformers called the “Australian ballot” (Australia was one of the first nations to adopt the secret ballot). Tweed was the boss of the notorious New York City political machine, Tammany Hall. Tammany and machines like it in other cities derived their power from their ability to garner the working-class vote. To ensure the masses voted “the right way,” Tammany employed legions of “shoulder hitters” (thugs who threatened voters with violence if they failed to vote for Tammany) to ensure that men voted for the machine. Because voters deposited colored ballots (to distinguish between the parties) and deposited them in glass spheres, shoulder hitters could easily spot any transgressors. Tammany punished wayward voters not only with violence, but also by firing them (or their family members) from public jobs or withholding charity from them.

Gradually reformers in the late nineteenth began to call for a revamping of voting practices to purify and revive American democracy. Some of these Progressive Era (1890-1920) reforms, such as the adoption of the referendum and initiative, as well as election primaries (to eliminate undemocratic nominations in smoke-filled rooms), are well known. Equally important, however, was the adoption of secret balloting. It made elections more democratic by freeing voters from coercion at the polls.

Follow me on Twitter @InThePastLane

In this cartoon from Reconstruction, Thomas Nast makes the case for granting voting rights to African Americans. Note how the recently freed slave and Union Army veteran reaches for the ballot box as he is set upon by racists determined to keep him (and all blacks) in a condition as close to slavery as possible.

Sources and Further Reading:

Kenneth D. Ackerman, Boss Tweed: The Rise and Fall of the Corrupt Pol Who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York (Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2005)

Oliver Allen, The Rise And Fall Of Tammany Hall (Da Capo Press, 1993)

Marchette Gaylord Chute, The First Liberty: A History of the Right to Vote in America, 1619-1850 (Dutton, 1969)

Robert J. Dinkin, Voting in Provincial America: A Study of Elections in the Thirteen Colonies, 1689-1776 (Greenwood Press, 1977)

Alexander Keyssar, The Right To Vote The Contested History Of Democracy In The United States (Basic Books, 2001)