InThePastLane by Edward T. O’Donnell

In recent years voters in many states have approved laws legalizing the recreational marijuana use (and that several other states approved medical marijuana use) has prompted much speculation that marijuana may some day enjoy the legal status of beer and cigarettes. In considering this possibility, it is instructive to look back a century, to a time when thousands of Americans joined a national crusade against the cigarette. By 1910 they had succeeded in banning cigarettes in 15 states and harbored high hopes of achieving a national ban in the coming years. And yet, within a few years the cigarette was well on its way to widespread use and extraordinary popularity. So what happened?

In recent years voters in many states have approved laws legalizing the recreational marijuana use (and that several other states approved medical marijuana use) has prompted much speculation that marijuana may some day enjoy the legal status of beer and cigarettes. In considering this possibility, it is instructive to look back a century, to a time when thousands of Americans joined a national crusade against the cigarette. By 1910 they had succeeded in banning cigarettes in 15 states and harbored high hopes of achieving a national ban in the coming years. And yet, within a few years the cigarette was well on its way to widespread use and extraordinary popularity. So what happened?

King James I of England was an early critic of tobacco smoking after the practice was introduced by Sir Walter Raleigh.

Smoking has always had its critics. One of the earliest and most memorable critiques—both for its poetic quality and invocation of a moral, religious, and health considerations—was that of King James I in 1603. Alarmed at the way English noblemen were taking to the habit following its introduction by Sir Walter Raleigh, he condemned smoking as, “A custome lothsome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmefull to the braine, dangerous to the Lungs, and in the black stinking fume therof, neerest resembling the horrible Stigian smoke of the pit that is bottomless.” Few heeded his advice to abstain and nearly three hundred years later, Englishmen and their American cousins annually smoked, chewed, and sniffed enormous quantities of tobacco. The critics who rose to challenge this growing obsession with tobacco were few and far between and they were generally ignored as health fanatics or puritanical evangelicals.

It was in the early 1880s, however, that the United States witnessed the rise of a new, vigorous, and widespread anti-smoking movement which lasted until the 1920s. While some of its members spoke out against all forms of tobacco, the great majority focused on a relatively new product: the cigarette.

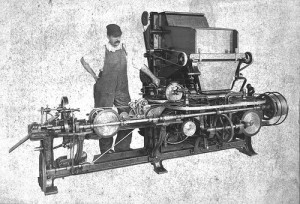

A worker stands by a cigarette rolling machine, ca. 1885. Invented by James A. Bonsack, this machine helped launch the cigarette industry.

As late as 1880 cigarettes comprised a barely visible fraction (less than one percent) of annual tobacco consumption, but the combination of James A. Bonsack’s invention of a mechanical cigarette making machine in 1880 and James B. Duke’s marketing genius set the stage for the cigarette’s rise to national prominence by the turn of the century. Whereas Americans consumed 500 million cigarettes in 1880, they consumed four billion by 1895 and sixteen billion by the eve of World War I.

Those who smoked cigarettes in this era were overwhelmingly working class city dwellers, many of them immigrants from southern and eastern Europe where the cigarette had already become popular. No city took to smoking cigarettes more than New York where by 1895 its citizens accounted for one quarter of the total national cigarette consumption.

Even as cigarette smoking remained on the fringes of tobacco use in the late nineteenth century, it managed to draw an unusually intense level of criticism and a steadily escalating call for its prohibition. In many ways this turn-of-the-century anti-cigarette crusade mirrored similar efforts to ban prostitution, boxing, gambling, and drinking. Indeed many of the movement’s members, like Carrie Nation, were active in these causes.

The formidable Lucy Gaston founded the Anti-Cigarette League in Chicago in 1890. It soon became a national movement.

By far the most prominent figure in the anti-cigarette crusade was Lucy P. Gaston who in 1890 established the Chicago-based Anti-Cigarette League of America. She and her like-minded supporters centered their argument against cigarettes on three principal issues. First, they condemned the cigarette as culturally unsuitable for Americans. They were symbols of the frivolous, effeminate, and foreign lifestyle of Europe. The New York Times, for example, argued in 1884 that “[t]he decadence of Spain began when the Spaniards adopted cigarettes” and warned that “if this pernicious practice obtains among adult Americans the ruin of the Republic is close at hand.”

Photographer Lewis Hine shot images of young boys smoking cigarettes to emphasize the harmful effects of child labor.

Second, prohibitionists also condemned cigarettes as uniquely tempting to working-class boys, in part because they were cheap (five cents for a pack of ten), small, mild, and quickly used. The cigarette habit, prohibitionists argued, was a “gateway” vice that set young boys on the road to a life of intemperance and addiction. “Where boys drink to excess,” opined one editorialist, “they are almost invariably smokers; and it is very rare to find a man over-fond of spirits who is not addicted to tobacco.” Eventually the cigarette led smokers to a life of crime. “The ‘cigarette fiend’ in time becomes a liar and a thief,” reported one New York City Board of Education official, “He will commit petty thefts to get money to feed his insatiable appetite for nicotine.” This notion was popularized by the tabloid press. “Charles Burton, aged 17, is to be hanged for murder,” the New York Telegram informed its readers in a typical notice, “He was a cigarette fiend.”

Finally, prohibitionists condemned cigarettes for their popularity among women. Though women were clearly a small minority of cigarette smokers at the turn of the century, they generated a disproportionate alarm from prohibitionists. They argued that young women, like boys, were susceptible to the allure of cigarettes which quickly drew them into a wider world of vice. As the Times put it, “The practice of cigarette-smoking among ladies seems to be generally regarded as the usual accompaniment of, or prelude to, immorality.” Curiously, no one seemed concerned that cigars, pipes, or chewing tobacco threatened the morality of men.

The anti-cigarette crusade achieved a remarkable degree of success in the first decade of the twentieth century. Hundreds of thousands joined the cause, including Thomas Edison and Henry Ford, both of whom declared publicly that they would not hire cigarette smokers. By 1910 fifteen states had banned the manufacture, sale, and use of cigarettes, leading many to dream that they might achieve total victory over the cigarette before temperance advocates defeated demon rum.

Cigarette prohibitionists believed they were on the verge of achieving a national ban on the “little white slaver,” but their optimism proved ill-founded for the anti-cigarette crusade soon went up in smoke. By 1908 cigarette smoking among wealthy woman, including President Roosevelt’s daughter, Alice, had already become a well established habit. “Passing an anti-cigarette law,” opined one observer in 1909, “seemed almost as ridiculous as it would to pass a law prohibiting a woman from wearing more than three pounds of false hair.”

During World War I the U.S. Army called upon the American people to donate cigarettes to the men serving overseas. Officials hoped this small vice would keep the “doughboys” occupied and out of French saloons and brothels.

Indeed, cigarette smoking among all Americans, regardless of age, class, or gender, would soar to astonishing heights in the coming decades. The popularity of cigarettes among American doughboys in World War I played a decisive role in transforming the cigarette from a subversive, effeminate, and dangerous product to a symbol of manliness, patriotism, and stylishness.

Sales soared to 45 billion in 1920 and kept rising, topping 484 billion in 1960. The appeal of cigarettes peaked in 1980 with sales of 632 billion. Rising health concerns and a reinvigorated anti-tobacco movement sparked a steady decline in sales to under 400 billion by 2007.

Today advocates of legalized marijuana point to the status of cigarettes as a model they hope will alleviate the concern among the general public over legalization. Cigarette consumption, they note, remains legal but the industry operates under heavy government regulation and taxation and within strict laws that prohibit most forms of advertising.

Follow me on Twitter @InThePastLane

Sources and Further Reading:

Allan Brandt, The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall, and Deadly Persistence of the Product That Defined America (Basic Books, 2009)

Richard Kluger, Ashes to Ashes: America’s Hundred‑Year Cigarette War, The Public Health, and The Unabashed Triumph of Philip Morris (Knopf, 1996).

Robert Sobel, They Satisfy: The Cigarette in American Life (Doubleday, 1978).

Cassandra Tate, The Cigarette Wars: The Triumph of the Little White Slaver (Oxford, 1999)

John K. Winkler, Tobacco Tycoon: The Story of James Buchanan Duke (Random House, 1942).