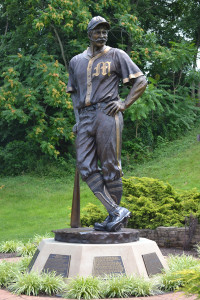

This statue of the Mighty Casey stands outside a ballpark in Williamsport, PA, home of the Little League World Series.

Athletic competition in the U.S. has produced many superb writers who have penned many gems of sports literature. Grantland Rice gave us “the Four Horsemen” and Roger Angell the “Boys of Summer.” But arguably the most famous piece of sports literature was not written by a seasoned journalist with thousands of hours in stadium press boxes. Rather, it’s the funny and endearing poem, “Casey at the Bat,” composed by a little-known newspaper humor writer.

The poem’s unlikely rise to fame began on August 14, 1888, when a young actor named DeWoIf Hopper stepped on stage in New York City and recited a humorous poem about a fictional slugger named Casey who, despite the hopes of the Mudville faithful, strikes out to end a big game. No one at the time, including Hopper and the man who penned the poem a few months earlier, knew just how famous the poem was to become – so famous, in fact, that statues of Mighty Casey are found all across the country, including one at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, NY.

“Casey at the Bat” was written by Ernest L. Thayer, a Harvard graduate of solid elite New England pedigree. He’d graduated from Harvard in 1885 and headed west to San Francisco at the urging of his fellow classmate, a young man named William Randolph Hearst who was about to take over a newspaper owned by his father. Thayer jumped at the chance to delay his inevitable return to his father’s textile mills in Worcester, MA and soon found himself writing humor and satire pieces for Hearst’s paper, the San Francisco Examiner. Three years later, with only weeks to go before he joined the family business back east, Thayer penned “Casey at the Bat: A Ballad of the Republic, sung in the year 1888.” He submitted it under the pen name “Phin” and received a mere $5 for his effort.

The poem was published in the Examiner on June 3, 1888. It became a hit in the Bay area and soon found its way into papers all across the country. But what really set it on its way to becoming one of the most well-known poems in American history its discovery by the manager of DeWoIf Hopper, a brilliant young actor who was then starring in “Prince Methusalem” at New York’s Walleck Theater. Knowing Hopper was scheduled to speak at an upcoming dinner honoring the New York Giants, his manager suggested he recite the poem. Hopper loved the poem and committed the 52 lines to memory. It proved such a hit at the Giants dinner, he soon began reciting it on stage (beginning on August 14, 1888), adding gestures and inflections that thrilled his listeners. “Casey” became Hopper’s signature act and he would recite it an incredible 10,000 times before his death.

The sign in Holliston, Massachusetts, one of several towns that claim to be the inspiration for the “Mudville” in Casey at the Bat.

Because Thayer used the pen name “Phin,” many imposters arose in the years to come claiming authorship – and royalties, of course. Some of the claims even went to court, prompting Thayer to admit his authorship. And, being wealthy and somewhat tired of the whole Casey business, eventually signed over the rights to Hopper. Many towns also laid claim to being the “real” Mudville, including Stockton, California and Holliston, Massachusetts. Stockton was once called Mudville and in 1888 (when Thayer was living in the state) was home to a professional ball club. Holliston had a neighborhood called Mudville and Thayer grew up only a few miles away in Worcester, MA. And is family owned a textile mill in the town very close to the Mudville baseball field.

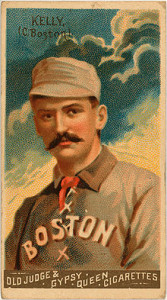

Not surprisingly, several players including Boston shortstop Tim Casey and Philadelphia pitcher Daniel Michael Casey, claimed they were Thayer’s inspiration (the latter Casey even hit the vaudeville circuit as the “real” Casey). Many others, not necessarily named Casey also claimed the honor, including famed slugger Mike “King” Kelly.

Finally in 1935, almost a half century after the poem’s publication, Thayer revealed that his inspiration for the fictional Casey had come from a high school classmate, a “big Irishman” named Daniel H. Casey who once threatened to beat him up for making fun of him in the pages of the school newspaper of which he was editor.

Apart from this reference, wrote Thayer, “the poem has absolutely no basis in fact. The verses owe their existence to my enthusiasm for college baseball.” As for the subsequent fame of the poem, he remained at a loss to explain it. “Its persistent vogue is simply unaccountable and it would be hard to say if it has given me more pleasure than annoyance.”

Thayer’s decision to make his hero an Irishman may also have been influenced by the simple

Mike “King” Kelly was one of the many Irish American stars in the early days of professional baseball.

fact that many of the most famous players in the early days of professional baseball were Irishmen. The aforementioned Mike “King” Kelly, for example, helped the Chicago Nationals win five championships in the 1880s. He led the league in batting in 1884 and 1886 and was a legendary base stealer, giving rise to the expression, “slide, Kelly, slide.” “Big” Ed Delahanty (one of five brothers who made the big leagues) posted a whopping career batting average of .346 and even hit four home runs in a single game. Roger Connor was the home run king of the so-called “deadball era,” with 192 round trippers over his career to go with twelve seasons with a batting average over .300. Joe Kelley was a standout left fielder for Baltimore in the 1890s, hitting over .300 in twelve consecutive seasons, including .391 in 1894. Pitcher Tim Keefe won 342 games in fourteen seasons, twice winning more than 40 games in a single season. Bud Galvin became baseball’s first 300-game winner and pitched more innings (5,959) and complete games (641) than anyone but Cy Young.

Ernest L. Thayer died in 1940, followed by Dewolf Hopper five years later. “Casey at the Bat,” however, just kept going. Actors such as Chuck Connors, Vincent Price, and Jackie Gleason recited it, Disney transformed it into a cartoon, the Post Office issued a “Mighty Casey” stamp (1996), Saturday Night Live parodied it, and magicians Penn and Teller used it in one of their acts – to name just a few of its latter-day incarnations. Today, a quick search at Amazon.com shows no less than 18 versions of the poem in print.

One reading (aloud, of course) leaves no doubt why.

Casey at the Bat

By Ernest L. Thayer (a.k.a. Phin)

San Francisco Examiner – June 3, 1888

The outlook wasn’t brilliant for the Mudville nine that day;

The score stood four to two, with but one inning more to play,

And then when Cooney died at first, and Barrows did the same,

A pall-like silence fell upon the patrons of the game.

A straggling few got up to go in deep despair. The rest

Clung to that hope which springs eternal in the human breast;

They thought, “If only Casey could but get a whack at that –

We’d put up even money now, with Casey at the bat.”

But Flynn preceded Casey, as did also Jimmy Blake,

And the former was a hoodoo, while the latter was a cake;

So upon that stricken multitude grim melancholy sat;

For there seemed but little chance of Casey getting to the bat.

But Flynn let drive a single, to the wonderment of all,

And Blake, the much despised, tore the cover off the ball;

And when the dust had lifted, and men saw what had occurred,

There was Jimmy safe at second and Flynn a-hugging third.

Then from five thousand throats and more there rose a lusty yell;

It rumbled through the valley, it rattled in the dell;

It pounded on the mountain and recoiled upon the flat,

For Casey, mighty Casey, was advancing to the bat.

There was ease in Casey’s manner as he stepped into his place;

There was pride in Casey’s bearing and a smile lit Casey’s face.

And when, responding to the cheers, he lightly doffed his hat,

No stranger in the crowd could doubt ’twas Casey at the bat.

Ten thousand eyes were on him as he rubbed his hands with dirt.

Five thousand tongues applauded when he wiped them on his shirt.

Then while the writhing pitcher ground the ball into his hip,

Defiance flashed in Casey’s eye, a sneer curled Casey’s lip.

And now the leather-covered sphere came hurtling through the air,

And Casey stood a-watching it in haughty grandeur there.

Close by the sturdy batsman the ball unheeded sped –

“That ain’t my style,” said Casey. “Strike one!” the umpire said.

From the benches, black with people, there went up a muffled roar,

Like the beating of the storm-waves on a stern and distant shore;

“Kill him! Kill the umpire!” shouted some one on the stand;

And it’s likely they’d have killed him had not Casey raised his hand.

With a smile of Christian charity great Casey’s visage shone;

He stilled the rising tumult; he bade the game go on;

He signaled to the pitcher, and once more the dun sphere flew;

But Casey still ignored it, and the umpire said “Strike two!”

“Fraud!” cried the maddened thousands, and echo answered “Fraud!”

But one scornful look from Casey and the audience was awed.

They saw his face grow stern and cold, they saw his muscles strain,

And they knew that Casey wouldn’t let that ball go by again.

The sneer has fled from Casey’s lip, the teeth are clenched in hate;

He pounds with cruel violence his bat upon the plate.

And now the pitcher holds the ball, and now he lets it go,

And now the air is shattered by the force of Casey’s blow.

Oh, somewhere in this favored land the sun is shining bright,

The band is playing somewhere, and somewhere hearts are light,

And somewhere men are laughing, and little children shout;

But there is no joy in Mudville – mighty Casey has struck out.