No document in U.S. history, except perhaps the Constitution, is more revered than the Declaration of Independence. Indeed, most Americans can recite (if not word for word) its prosaic lines, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Ignored at first, the Declaration of Independence became a sacred text in American political culture.

But today’s reverence for the Declaration obscures two important and fascinating details regarding the document’s early history:

1. Few, if any, Americans in 1776 cared about the beautiful and uplifting words from the Declaration quoted above. They understood the document for what it was: a practical DECLARATION OF WAR and not a lofty proclamation universal equality and human rights

2. It took years—decades, actually—for the Declaration of Independence to be considered a sacred text of the Founding era.

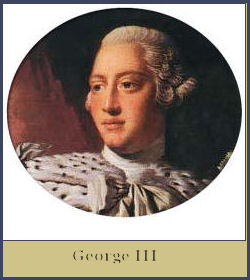

So let’s examine these two points in some detail. Why didn’t most Americans in 1776 care about the beautiful opening section to the Declaration of Independence that modern Americans hold so dear? The answer is simple. They saw it as a flowery introduction and were far more concerned with what followed: the list of grievances against King George III that justified independence. This section took up about two-thirds of the Declaration and included more than two dozen complaints directed specifically against George III.

The Declaration of Independence targeted George III and his violation of American liberties as the cause of the American Revolution.

Here are a few representative examples:

He has refused his assent to laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

He has made judges dependent on his will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.

He has erected a multitude of new offices, and sent hither swarms of officers to harass our people, and eat out their substance.

He has affected to render the military independent of and superior to the civil power.

He has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.

So, to Americans in 1776, the Declaration of Independence was inspirational only in so far as it made the case to the world for breaking with the Mother Country and defending that decision with arms. Later generations of Americans, long after the Revolutionary War’s successful conclusion, would care far less about this indictment of George III and far more about the Declaration’s vivid articulation of the ideals of universal equality and human rights.

So when did this happen? Certainly not right away. Indeed, for the first few decades after July 4, 1776 few Americans considered the Declaration a great document. When they celebrate the Fourth of July, they celebrated the act of declaring, not the document itself

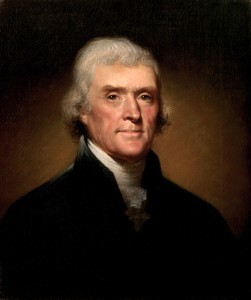

Originally, few people knew that Thomas Jefferson had penned the Declaration. Only when its significance grew did Jefferson and his supporters proclaim this fact.

So when did Americans come to revere the Declaration as one of the nations most sacred texts? It began in the 1790s. That decade was dominated by Federalists (Adams, Hamilton, etc) who downplayed the significance of the Declaration because they disliked its anti-British tone and found alarming the similarity of its language with Revolutionary France’s “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.” In contrast, their emerging political opposition, the Jeffersonian Republicans, came to see themselves as defending the “Spirit of 1776” and the Revolution against Federalists whom they viewed as not only pro-British but also pro-monarchy. As a result, Republicans in the 1790s began reading Declaration of Independence at July 4th celebrations and quoting it in speeches. They also took to celebrating the Declaration’s author, Thomas Jefferson. In so doing, they emphasized the Declaration as a Founding document that condemned monarchy and privilege, and celebrated liberty and equality. So when the Jefferson and the Republicans came to power in 1801, they saw to it that the Declaration of Independence became firmly enshrined as the nation’s great founding document. With each passing year, the reputation of and reverence for the Declaration grew.

By the1820s Jefferson himself came to realize that the Declaration was the centerpiece of his legacy. So when he arranged for the inscription on his tombstone, he decided it would read: “Here was buried Thomas Jefferson, Author of the Declaration of Independence, of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom and Father of the University of Virginia.”

Then, just in case anyone doubted the importance of the Declaration, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams died on its 50th anniversary: July 4, 1826. And for good measure, Pres. James Monroe died five years later on July 4, 1831. You can’t make this stuff up!

Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote the Declaration of Sentiments and presented it to the first women’s rights convention, held at Seneca Falls in 1848.

But, the evolution of the Declaration’s meaning and significance continued long after Jefferson’s death. Women’s Rights activists at the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, for example, created the “Declaration of Sentiments” which said: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men and women are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights …”

Similarly, abolitionists, labor activists, and other reformers invoked the Declaration to justify their demands.

President Abraham Lincoln played a key role in the transformation of the Declaration into a sacred document. In his Gettysburg Address on November 19, 1863 he invoked the Declaration: “Four score and seven years ago [1776] our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

Rev. Martin Luther Kin invoked the Declaration of Independence in making his claim for equality for all Americans regardless of race.

A century later, in his stirring call for civil rights in his “I Have A Dream” speech in August 1963, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. said, “In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the ‘unalienable Rights’ of ‘Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.’ … And so, we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice…”

Although it was not his primary intention back in July 1776, Jefferson gave voice to the radical idea that we all have rights. Since that time it’s been left it to succeeding generations, and the democratic process, to define, secure, and protect them.

Sources and Suggested Reading:

Benson Bobrick, Angel in the Whirlwind: The Triumph of the American Revolution (1995)

Philip S. Foner, ed., We, the Other People: Alternative Declarations of Independence by Labor Groups, Farmers, Woman’s Rights Advocates, Socialists, and Blacks, 1829-1975

Pauline Maier, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (1997)

Garry Wills, Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America (1992)

Gordon Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (1991).