InThePastLane.com by Edward T. O’Donnell

The Red Scare and the Boston Police Strike of 1919

The year 1919 was one “those years” in American history — like 1776, 1860, 1946, 1968, and 2001 — one racked by social upheaval and fear. Indeed, 1919 ushered in a two year period known as the “red scare” that saw a wave of anti-radical hysteria sweep the nation in response to record numbers of strikes and mysterious bombings. One of the events that year that suggested to many Americans that radicalism was threatening the nation was the Boston Police Strike.

It all began on September 9, 1919 when more than eleven hundred members of the Boston Police Department (72%) went out on strike. For years the city’s policemen had labored under dreadful conditions for low pay. But all their pleas for reform over the years had fallen on deaf ears. Matters reached the breaking point in 1919 when nineteen officers were suspended from the force for their role in establishing a policemen’s union. As an act of solidarity, nearly three out of four policemen took part in the strike. It was a bold maneuver for such men in a city dominated by a conservative elite that was hostile to labor unionism. And to make matters worse for the police, that elite was comprised of wealthy Protestants (“Brahmins” as some called them) while the police force was made up largely of Irish Catholics, a group the elite loathed.

The men employed by the Boston Police Department had been forced to endure harsh working conditions and abysmal pay for decades before 1919. In 1906 Police Commissioner Stephen O’Meara founded the Boston Social Club, a fraternal organization dedicated to improving this situation. Unfortunately, all their calls for reform fell on deaf ears. By the summer of 1919 the Club’s leaders concluded that their only hope lay in forming a union and joining the American Federation of Labor. They founded the Boston Policemen’s Union in mid-August 1919.

Their decision made sense on one level. The AFL was the nation’s largest labor organization with a proven record of successful organizing workers and winning strikes. Yet there was one problem: 1919 was a year of unprecedented labor strife. The end of World War I in late 1918 signaled the end to a period of robust economic growth. It also meant that many employers who had been pressured by a federal government eager for labor peace during the war to recognize unions, reduce hours, and increase pay now withdrew these concessions. Outraged and determined not to let their wartime gains slip away, some four million of workers went on strike in 1919. Wealthy and middle-class Americans were alarmed by the scale of working-class discontent and many believed it was a sign that anarchism, socialism, and communism were on the march in America. Labor leaders were castigated as dangerous radicals and arrested by the thousands. By mid-1919 the nation was convulsed not only in worker strife, but also a counter-reaction that came to be known as the Red Scare. In short, forming the Boston Policemen’s Union in August 1919 was an extraordinarily risky decision.

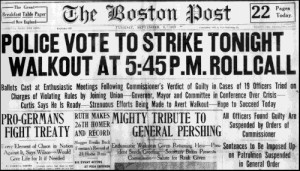

That fact quickly became evident. Police Commissioner Edwin Curtis, a member of the Yankee elite, announced that he would not recognize any policemen’s union. Indeed, in anticipation of the union’s formation, he changed the Police Department’s regulations to forbid policemen from being members in any outside organization. On August 26, Curtis notified nineteen policemen that they would face disciplinary hearings regarding their membership in the new union. Two weeks later, on September 8, he announced that the men were suspended. The Policemen’s Union called a meeting where the men overwhelmingly voted to go on strike.

The strike began the next day at 5:45 p.m. at the nightly shift change and roll call. Things began to go awry for the strike almost immediately. As word of the strike spread across the city, crowds gathered downtown. Shortly after 8:00 p.m. a group of young men kicked in the door of a tobacco store and looted it. Immediately hundreds more followed suit, smashing windows, looting stores, and attacking passersby. With only slightly more than one-fourth of the police force on duty, the rioting spread in all directions.

And here’s where the Boston Police Strike had a major impact on U.S. history. The governor of Massachusetts, a little-known man named Calvin Coolidge, mobilized the state regiments of the national guard and sent them to restore order in Boston. President of the AFL, Samuel Gompers, telegraphed Coolidge and suggested a compromise: the striking policemen would return to work if the city agreed to address their grievances. Coolidge answered with a terse statement that would soon make him famous: “There is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, anytime.”

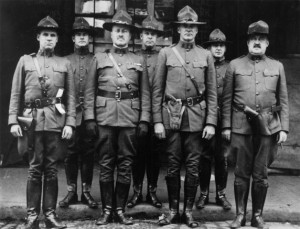

Massachusetts governor Calvin Coolidge inspects members of the state militia he ordered into Boston to restore order.

The rioting and mayhem lasted for three days and left eight dead. Proper Bostonians seethed with anger at the striking policemen, anger that was fueled to a significant degree by the longstanding animosity that existed between the city’s Protestant Yankee establishment and the immigrant Irish. The former cheered when Boston officials announced that all the striking policemen were fired and their places taken by “husky Yankee boys,” many of them World War I veterans. “Good American Yankees,” asserted one official, “do not strike!”

The strike, which ended in total defeat for the policemen, played a key role in national politics. Few Americans had ever heard of Calvin Coolidge before the strike, but his iron-fisted handling of the dispute made him a national celebrity among those fearful of the rising tide of labor radicalism. Eager to recapture the White House after eight years of Democrat Woodrow Wilson’s administration, the Republican party put Coolidge on the national ticket in 1920 as the vice-presidential candidate with Warren G. Harding. The conservative duo won the election and when Harding died eighteen months later, “Silent Cal” Coolidge was sworn in as President of the United States.

Sources and Further Reading:

Thomas H. O’Connor, The Boston Irish: A Political History (1997)

Stephen Puleo, Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919 (2003)

Francis Russell, A City in Terror: The 1919 Boston Police Strike (1977)