InThePastLane.com by Edward T. O’Donnell

Historians like to describe the American Civil War as the first “modern” war, in large measure

Photography was relatively new when the Civil War began. This is one of the cameras used by Mathew Brady.

because of the central role played by new industrial technology. The telegraph, for example, allowed for instant communication across vast territory. Railroads made it possible to shift thousands of reinforcements hundreds of miles in less than a day. Ironclad ships revolutionized naval strategy, while hot air balloons held out the possibility of high altitude reconnaissance. Above all, what made this war different from all previous ones was the level of carnage made possible by advances in weaponry. Artillery became more accurate and deadly, while antipersonnel landmines appeared for the first time. Both armies used improved rifled muskets capable of killing a man 400-500 yards away (vs. 100 yards for traditional muskets). Little wonder then, that the four year conflict claimed the lives of more than 700,000 men.

But not all technological innovations that shaped the Civil War were military in nature. Great advances in photography allowed Americans to see what traditionally had been left to the imagination or an artist’s pen or brush: actual images of war’s carnage and destruction. Photography was first invented in the late 1830s in France and gained popularity in the United States in the 1840s and 1850s. At first, owing to the long time needed for exposure, most photographs were indoor studio portraits.

America’s leading studio photographer at the time of the Civil War was Mathew Brady. Born in upstate New York in 1823, he first studied painting before turning in the early 1840s to a form of photography called the daguerreotype. In 1844 Brady opened a lavish Daguerrean Miniature Gallery on lower Broadway in New York. Business boomed, and within five years Brady became a highly regarded portraitist. In 1849 he opened a studio in Washington, D.C., and the next year published Gallery of Illustrious Americans, a book featuring the portraits of 24 prominent individuals, including U.S. presidents, inventors, and writers. By 1860 he owned large galleries in Washington and New York.

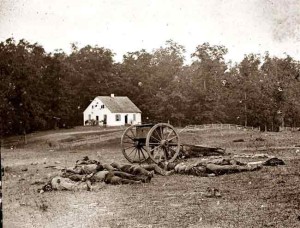

When the war came, Brady assembled his team of more than thirty assistants and sent them to photograph the conflict. Initially, they mainly photographed Union officers or scenes of camp life. That changed with the battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, an epic clash between Union and Confederate forces that saw nearly 25,000 men fall dead or wounded. The next day Brady sent two of his assistant photographers, Alexander Gardner and James F. Gibson, to the battlefield. There they took hundreds of photographs of the battle’s aftermath. Most focused on the bleak landscape littered with thousands of fallen soldiers.

Alexander Gardner’s photograph of the aftermath of Antietam. Here fallen soldiers lie strewn on the ground with a Dunker church in the background.

Gardner’s and Gibson’s photographs shocked the American public. The grim scenes of carnage and destruction challenged the romanticized visions of war shared by many citizens when the conflict started. They delivered a blunt unambiguous message to their viewers: the men pictured here may have died gallantly, but they also died in a brutal manner, shredded by cannon fire and pierced by bullets, and then splayed in irregular and undignified poses in the cold dirt.

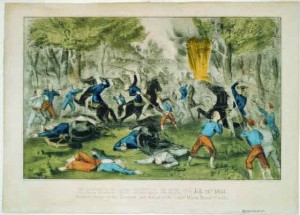

Currier & Ives issued this print of the Battle of Bull Run in 1861. Its romanticized view of war was typical of the era.

Note the contrast between the Gardner and Gibson photographs and this popular Currier & Ives illustration of the First Battle of Bull Run published one year earlier when most Americans still held to the belief that the war would be short, glorious, and victorious. Unlike the brutal scenes of death captured by the camera, the artist’s depiction of war shows several men who have fallen, but their uniforms remain spotless, with no trace of blood. The print’s caption describes the scene as a “Gallant charge,” reflected the popular notion that war romantic and heroic.

A few weeks after the Battle of Antietam, Brady put the grim collection of photographs on

display in his New York gallery under the title “The Dead of Antietam.” Tens of thousands paraded by the exhibit in astonishment. For generations people on the home front had relied upon writers and artists like the one employed by Currier & Ives to convey the scenes of conflict and carnage. Now photographers could capture such images in unprecedented detail and realism. “The dead of the battle-field come up to us very rarely, even in dreams,” commented the New York Times, “We see the list [of casualties] in the morning paper at breakfast, but dismiss its recollection with the coffee … Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought the bodies and laid them in our door-yards and along streets, he has done something very like it.”

The world would never “see” war in quite the same way again.

Gardner captioned this photo, “A Contrast: Federal buried, Confederate unburied, where they fell on the Battle-field of Antietam.”

Follow me on Twitter @InThePastLane

Sources and Further Reading:

William C. Davis, The Civil War in Photographs (Seven Oaks, 2008)

Alexander Gardner, Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the Civil War (Dover, 1959)

Mary Panzer, Mathew Brady and the Image of History (Smithsonian Books, 2004)

Theodore P. Savas, Brady’s Civil War Journal: Photographing the War 1861-1865 (Skyhorse Publishing, 2008)

Stephen W. Sears, Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam (Ticknor & Fields, 1983)

Wayne Youngblood, Mathew B. Brady: America’s First Great Photographer (Chartwell Books, 2008)