InThePastLane.com by Edward T. O’Donnell

Columbus Day marks not only the anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the Americas, but also the birth of the Pledge of Allegiance. The story of how this civic ritual—one performed by millions of Americans every week—is largely unknown. That’s unfortunate, because it is both a fascinating story and one from which we can draw important insights into the nature of social customs and the ideas that underlie them.

Columbus Day marks not only the anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the Americas, but also the birth of the Pledge of Allegiance. The story of how this civic ritual—one performed by millions of Americans every week—is largely unknown. That’s unfortunate, because it is both a fascinating story and one from which we can draw important insights into the nature of social customs and the ideas that underlie them.

So where did The Pledge come from? Before answering that question, let’s consider the nature of “tradition.” As a historian, I’ve developed a series of unofficial “rules” about history that I am fond of reciting to my students or public lecture audiences. Two of them are appropriate to this week’s topic. First, nothing is as old as you think it is—by which I mean the practices, traditions, and customs a society deems sacred because “we’ve always done it that way” turn out, upon closer investigation, to be of relatively recent vintage. The veneration of segregation during the Jim Crow era or the happy suburban housewife of the 1950s provide vivid examples. Second, nothing “has always been”—by which I mean the aforementioned practices, traditions, and customs are never fixed; rather they are forever evolving both in form and meaning. One need only consider how profoundly the celebration of Christmas in the United States has changed over the past two centuries.

Both these “rules” apply to the story of The Pledge. First, it’s not nearly so ancient a ritual as many Americans would believe. It was written in 1892, long after the Founding Fathers had passed from the scene. Indeed, the United States had flourished without it for over a century. Second, the text of The Pledge itself has been changed on two occasions. And the method of saluting the flag during The Pledge has also been altered.

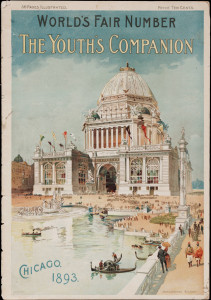

The Pledge, considered by most Americans their most sacred ritual of patriotism, was actually written by a socialist. Francis Bellamy, a fervent Christian socialist and brother of the famed writer Edward Bellamy, penned the original pledge for the Youth’s Companion, a popular youth magazine. For several years the magazine had been championing a movement to place American flags in every school. The effort reflected the editor’s patriotism, but also his keen business sense because the Youth’s Companion offered a free flag to any school that purchased a subscription.

In 1891 the magazine’s editor hit upon the idea of boosting flag and subscription sales by creating a pledge of allegiance to be recited by school children across the nation. To draw attention to the initiative, the Youth’s Companion announced that The Pledge would debut on Columbus Day, 1892, a day that marked the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ arrival in the New World and the opening of the Chicago World’s Fair (the fair actually did not open until 1893).

The Youth’s Companion created and published The Pledge of Allegiance in the fall of 1892 with the goal of having all American school children recite it on Columbus Day.

Tying the debut of The Pledge to all the national hoopla surrounding the Columbus Day celebration proved a brilliant move. Soon after The Pledge appeared in the September 8, 1892 edition of the Youth’s Companion, thousands of schools committed to reciting it the following month on Columbus Day.

Bellamy’s pledge also came with instructions for a salute to be carried out during the recitation.

“At a signal from the Principal the pupils, in ordered ranks, hands to the side, face the Flag. Another signal is given; every pupil gives the flag the military salute—right hand lifted, palm downward, to a line with the forehead and close to it. Standing thus, all repeat together, slowly, ‘I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands; one Nation indivisible, with Liberty and Justice for all.’ At the words, ‘to my Flag,’ the right hand is extended gracefully, palm upward, toward the Flag, and remains in this gesture till the end of the affirmation; whereupon all hands immediately drop to the side.”

Two aspects of The Pledge are worth noting. The wording is considerably shorter than the current version of The Pledge in use today. And the practice of extending an arm upward to the flag at the end was later replaced, for reasons discussed below, with simply placing the hand over one’s heart.

To the delight of Bellamy and the editors of the Youth’s Companion, The Pledge took on a life of its own after its debut. Educators made recitation of The Pledge a frequent (and eventually daily) ritual in schools across the country. Civic and veterans organizations soon adopted it and before long it became a standard opening ritual at events like July 4th celebrations and graduations.

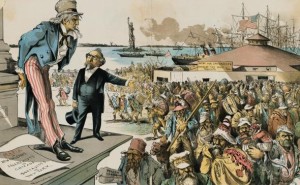

Widespread fear of immigrants as bearers of dangerous radical ideologies like socialism is captured in this 1891 cartoon.

Underlying this embrace of The Pledge was a profound fear among native-born Americans over mass immigration. It is not entirely a coincidence that Ellis Island, a facility dedicated to screening out undesirable immigrants, opened the same year The Pledge debuted. Americans feared not merely the cultural, linguistic, and religious differences of the record levels of immigrants arriving in the 1890s. They also feared what they perceived as a clear connection between immigrants and radical ideologies such as socialism, communism, and anarchism. The United States experienced its most intense and deadly period of labor-capital conflict in its history between 1880 and 1920 and many Americans were convinced that much of the unrest stemmed from the introduction of un-American ideas by immigrants. Introducing The Pledge into public schools reflected an effort to Americanize the urban immigrant masses by teaching them, in addition to the “three R’s,” patriotism, loyalty, and respect for democracy and the law.

Fear of radicalism and disloyalty soared during and after World War I and led to more changes in The Pledge. In 1923 a patriotic organization called the National Flag Conference issued a call for The Pledge’s wording to be expanded to read:

“I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the United States and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

The proposed changes reflected the fear that immigrants might be secretly pledging loyalty to the flags of their homelands. A year later, as Congress put the finishing touches on a law that dramatically reduced immigration to the United States, the Conference urged the addition of “of America” to The Pledge. Both changes were immediately adopted by the public.

The original flag salute as described by Francis Bellamy. Because it bore an unwanted resemblance to salutes used in fascist Italy and Germany, it was replaced with the hand over the heart.

The next significant alteration came during World War II. By that time Bellamy’s extended arm salute bore an unwanted resemblance to the salutes used in fascist Germany and Italy. Pledge advocates replaced the salute with the placement of the right hand over the heart. It was also during World War II that Congress declared (in 1942) The Pledge the official declaration of loyalty to the United States.

The last change to The Pledge came in 1954, at the height of the Cold War. Several national organizations, notably the Sons of the Revolution and the Knights of Columbus, launched campaigns in the early 1950s to have the words “under God” inserted into The Pledge to read:

“I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

The campaign reflected a key Cold War theme, that of depicting the United States as a democratic, capitalist, and Christian society in stark contrast to a totalitarian, communist, and Godless Soviet Union. President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed a bill making this change official on Flag Day, 1954.

The Pledge of Allegiance remains a central feature of civic events in America, most especially ceremonies where immigrants become U.S. citizens.

The story of The Pledge reminds us that all traditions are invented and often more recently than is widely believed. It also reminds us that all such traditions evolve in ways that reflect the needs of particular eras.