“The First Thanksgiving at Plymouth” by Jennie A. Brownscombe (1914) presents a typical mythologized scene showing Plymouth settlers celebrating Thanksgiving with Wampanoags (dressed in the garb of Plains Indians!).

As Thanksgiving approaches, we can expect many newspaper articles and television programs detailing the story behind the holiday’s origins. The accurate ones will explain how the first Thanksgiving in 1621 bore little resemblance to the scenes represented in paintings—e.g., Pilgrims and Native Americans seated at long tables eating roast turkey and pumpkins. Many will also point out that Thanksgiving only became a national holiday in 1863 during the Civil War and even then it took decades more for the South to begin celebrating it.

But few if any will delve into the essential backstory behind the first Thanksgiving celebrated in Plymouth, Massachusetts: the devastating epidemic of plague that ravaged the Native population just before the arrival of the first permanent English settlers. This catastrophe so weakened the local Wampanoag Indians that it played a direct role in their decision to make peace with the Pilgrims and to help them survive—the decisions that earned them an invitation to a feast of thanksgiving in 1621.

The Great Epidemic of 1616-1619 had its origins with a shipwreck. In 1615 a French trading vessel wrecked off the coast of Massachusetts, somewhere on Cape Cod near present-day Plymouth. The local Wampanoag Indians, who’d seen many of their people (including the famous Squanto) kidnapped by European traders in recent years, killed all the survivors except for four men who they turned into slaves. At least one of these French captives carried the disease that caused the Great Epidemic.

To Europeans like these captive Frenchmen, this disease—long thought to be typhus, small pox, or plague, but recent research suggests was leptospirosis—had posed only a minor health threat. Europeans had been exposed for centuries to these and other ailments. While many died, succeeding generations developed immunities and resistance to these diseases.

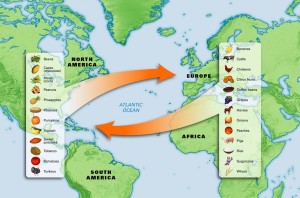

The “Columbian Exchange” saw the transfer between the Old World and the New of a great many plants and animals, but also diseases.

For Native Americans, however, it was a different story. Their world had never seen these diseases. When “continental drift” began 120 million years ago, it transformed one large megacontinent into the separate continents of Europe, Africa, Asia, Oceana, and North and South America. These separate habitats saw the rise of unique animal and plant species (in Europe and Africa: horses, cows, pigs, sheep, chickens, honey bees, wheat, rice, and citrus fruits; in the Americas: potatoes, corn, squash, pumpkins, tomatoes, peppers, peanuts, sunflowers, tobacco, and turkeys). Once the age of European exploration began in the late-15th century, these animals and plants crossed the Atlantic in a process historians term, “The Columbian Exchange.” Unfortunately, it also included diseases unique to each region. While many Europeans suffered from the introduction of syphilis from the Americas, the peoples of the Americas were devastated by cholera, typhus, small pox, and plague wherever Europeans made contact. It was conquest, in the words of historian Alfred Crosby, the man who also coined the term Columbia Exchange, by “an arsenal of diseases.”

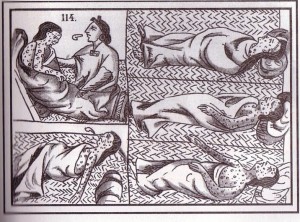

This image comes from a book written about the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. Everywhere in the New World the greatest killed of native peoples was European diseases.

And so, when the disease began to spread from the French captives to the Wampanoags, the latter sickened and died with alarming speed. Once the epidemic took hold in 1616 it raged for 4 years (some accounts note three successive epidemics). How devastating was it? According to later accounts by traders, Pilgrims, and Natives (and confirmed by modern researchers), the epidemic wiped out as much as 90% of the Native population in southern New England. Of the approximate 8,000 Wampanoags living near Plymouth in 1600, fewer that 2,000 survived in 1620.

We get a sense of the scale of devastation from a vivid account recorded by a captain Thomas Dermer. He traveled from present-day Maine to Massachusetts in 1619 and when he arrived he found, “ancient plantations, not long since populous, now utterly void; in other places a remnant remains, but not free of sickness.”

Another account of devastation was recorded two years later in 1621 by a party of Pilgrims who were out exploring about 15 miles from Plymouth. They found many abandoned villages and overgrown Native cornfields. One of them wrote, “Thousands of men have lived there, which died in a great plague not long since.”

Near the site that became Boston, a man named Thomas Morton wrote that so many Natives had died, and died so suddenly, that many bodies were left unburied. As a result, the surrounding woods were filled with, “[So many bones and skulls] that as I traveled in that Forrest, … it seemed to me a newfound Golgotha.” Golgotha, of course, was the place referred to in the Bible where Jesus was crucified. It meant “place of the skull.”

French explorer Samuel de Champlain found southern New England brimming with robust Native American populations in 1605 – eleven years before the Great Epidemic struck.

To put all this in perspective, back in 1605 (eleven years before the start of the Great Epidemic), French explorer Samuel D. Champlain explored southern New England looking for potential sites to establish a French colony. He rejected the region because the native population was so numerous and frequently hostile. But just 15 years later in 1620, when a group of English religious dissenters that we know as the Pilgrims landed in the same region, they found a much-reduced Indian population and many abandoned Indian settlements and farms.

There was another impact of Great Epidemic beyond sharply reducing the Native population: it left the surviving Wampanoags terrified of Europeans and of their God whom they presumed had sent the epidemic top wipe them out. This fear is significant because during the first winter of 1620-1621, fully half the Pilgrims died malnutrition, exhaustion, and exposure. The remaining Wampanoags, even after the Great Epidemic, still greatly outnumbered the English. They could easily have wiped out the settlement and made Plymouth one of the “lost colonies” like Roanoke Island.

And yet–no attack came because the Wampanoags apparently feared the wrath of the white man’s God. One visitor to Plymouth in 1621, a man named Robert Cushman, observed that the Great Epidemic seemed to sap the Indians of courage. “[T]heir countenance is dejected,” he wrote, “and they seem as a people affrighted” even though they “might in one hour have made a dispatch of us, yet such a fear was upon them, … that they never offered us the least injury in word or deed.”

It was this fear of the Pilgrims, plus additional concerns about the threat posed by the powerful Narragansett Indians to the south, that prompted the Wampanoag leader Massasoit to make peace and establish an alliance with the Pilgrims in the spring of 1621. That spring and summer the Wampanoags taught the Pilgrims what to plant and how to hunt certain wildlife and fish. And that’s why they were invited to the first Thanksgiving in the Fall of 1621.

Yet another idealized and historically inaccurate depiction of the first Thanksgiving– “The First Thanksgiving,” by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, ca. 1912

All this ads up to a considerably more complicated version of the first Thanksgiving story than we’re used to. Had there been no Great Epidemic, it seems likely that the Pilgrims, had they survived and managed to have anything to be thankful for, would have celebrated the first Thanksgiving among themselves.

Follow me on Twitter @InThePastLane

Sources and Further Reading:

S. F. Cook, “The Significance of Disease in the Extinction of the New England Indians,” Human Biology (1973) 45: 485–508.

John S. Marr and John T. Cathey, “New Hypothesis for Cause of Epidemic among Native Americans, New England, 1616–1619” Emerging Infectious Disease (Feb 2000) http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/16/2/09-0276.htm

William Cronon, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists and the Ecology of New England (New York: Hill & Wang; 1983).

Donald R. Hopkins, The Greatest Killer: Smallpox in History (University of Chicago Press, 2002).

Charles C. Mann, 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus (Knopf, 2005)

Charles C. Mann, 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created (Knopf, 2011)

George Rosen, “Epidemics in Colonial America,” American Journal of Public Health and the Nations Health 44.2 (February 1954)

Michael Willrich, Pox: An American History (Penguin, 2011)