InThePastLane by Edward T. O’Donnell

Sanger spoke often in favor of birth control. Occasionally her opponents managed to have her lectures cancelled. In this photo, Sanger put on a gag to protest her being banned in Boston in 1929.

Americans have spent a lot of time and energy in recent years arguing about birth control. The debate has centered not on the morality of contraception, but rather, in the wake of the Affordable Care Act’s mandate that employers’ health insurance must cover contraception, who should pay for it. While we wait for the matter to be settled in the courts, it’s instructive to look back on the history of birth control in the United States.

For it was a mere 96 years ago this week in 1916 that Margaret Sanger and several other women were arrested and thrown in jail for opening the nation’s first family planning clinic. Sanger was undaunted and thanks to her efforts, American women eventually gained full access to birth control. Indeed, Sanger lived long enough to play a key role in the development of The Pill.

Margaret Sanger was born Margaret Higgins in 1879 in Corning, NY, the sixth of an eventual eleven children. Her parents provided two very different inspirations for the radicalism that would one day make her famous. Her father, an atheist, set her on the path to rejecting all religious authority. Her mother, a devout Catholic, died at age 48—a direct result, Sanger always believed, from the physical toll of bearing and raising eleven children. This tragedy compelled her to find a way to empower women to control how many children they chose to bear.

More than a million New Yorkers lived in squalid tenements in the early 20th century when Margaret Sanger began working among the poor as a nurse. This photo was taken by Jesse Tarbox Beals.

Sanger attended college for two years (1894-1896) and then studied nursing at White Plains Hospital in New York. In 1902 she married William Sanger, an architect, and started a family (they eventually had three children). As a nurse Sanger worked in the slums of New York, ministering to the immigrant poor who lived desperate lives in unhealthy tenements. This work brought her into contact with reformers and settlement house workers and eventually, with a community of radicals living in Greenwich Village. This group included legendary radicals like Emma Goldman, John Reed, and Eugene Debs. Sanger soon joined the Socialist Party and worked on behalf of women’s rights and other radical causes, all the while continuing to work as a nurse among the poor.

It was in the course of her daily visits to the impoverished families of the Lower East Side that Sanger began to focus on what would become her life’s work. Increasingly she came to believe that women’s emancipation from inequality, poverty, and poor health would only occur when women learned how to prevent pregnancy and limit the size of their families

Anthony Comstock, the nation’s leading purity crusader in the late 19th century, successfully lobbied Congress to pass legislation barring the use of the US mail to send “immoral” and “indecent” materials, including information about contraception.

There was, of course, one problem. Most Americans in the early twentieth century, regardless of religious denomination, opposed contraception. They believed it would undermine the family and promote immorality. The Comstock Law, passed back in 1873, prohibited the distribution of information about contraception through the mail. By 1914 some twenty-two states had laws that similarly curbed the distribution of such information.

Undaunted, Sanger plunged into the study of contraception and in 1914 started a radical newspaper aptly named, The Rebel Woman, with a masthead that included the slogan “No Gods, No Masters.” From its pages Sanger urged women to stand up for their rights and to “act in defiance of convention.” At the same time she published a pamphlet on contraception entitled “Family Limitation” in which she coined the phrase “birth control.” But when the police shut down her paper and seized copies of her pamphlet, Sanger fled the country for Europe to avoid arrest.

Sanger established The Woman Rebel in 1914 to advocate for women’s rights, including the right to contraception.

She returned eighteen months later (after the indictment against her had been dropped) committed to a new strategy. Recognizing the broad cultural and political conservatism that suffused much of American society, Sanger decided it was unwise to present birth control as a revolutionary feminist demand. Rather, she would promote it as a basic medical necessity. Physicians, she argued, should be allowed to provide information on contraception just as they did other forms of medical advice.

But Sanger was not content to wait for the anti-contraception laws to change. On October 16, 1916 she joined with her sister Ethyl Byrne, and a third woman named Fannie Mindell, to open a family planning clinic in Brownsville, a largely immigrant and working-class neighborhood in Brooklyn. In reality, it was little more than a storefront operation that offered free counseling, medical consultations, and literature on contraception techniques. No contraceptive devices (such as they existed) were distributed. Nonetheless, the police soon raided the facility and threw the women in jail for thirty days.

Despite this setback, the winds of change began to blow in Sanger’s favor. The judge who upheld her 30-day sentence sided with her contention that physicians be granted greater freedom to disseminate information on contraception to their patients. Inspired by this development, Sanger soon published a book on contraception, What Every Mother Should Know (1917). She also founded the Birth Control League to lobby for legal reforms regarding doctors and contraception. In 1921 she took this effort nationwide with the founding of the American Birth Control League. With remarkable speed, Sanger’s crusade to legalize birth control gained popular support.

Sanger spoke often in favor of birth control. Occasionally her opponents managed to have her lectures cancelled. In this photo, Sanger put on a gag to protest her being banned in Boston in 1929.

Sanger’s greatest opposition came from the Catholic Church which stood by its traditional teaching against contraception. Sanger’s chief antagonist was Monsignor John A. Ryan, a priest many considered quite radical for his writings in defense of labor unions and a living wage. Despite his progressive positions on most social issues, on the matter of birth control Ryan stood firmly on conservative ground, defending Church teachings and denouncing Sanger’s crusade as a distraction from real social reform causes. “To advocate contraception,” Ryan told a congressional committee, “as a method of bettering the condition of the poor and unemployed, is to divert the attention of the influential classes from the pursuit of social justice.”

Others would find different reasons to criticize Sanger. Initially, she supported birth control as a means of liberating women and raising the health and living standards of the poor. But she soon grew increasingly infatuated, as did many Americans in this era (and later Hitler and the Nazis), with eugenics, a movement that championed “race improvement” by reducing (via forced sterilization) the population of groups deemed genetically inferior. Birth control, Sanger declared, would reduce the population of undesirable immigrants and racial groups. “More children from the fit,” Sanger wrote in 1919, “less from the unfit — that is the issue.” Sanger eventually rejected these views.

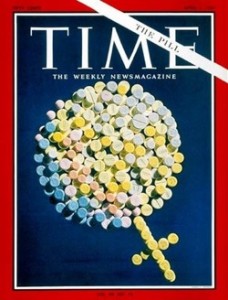

Despite unbending opposition from many quarters, Sanger and her crusade continued to gain public support. In 1942 the Birth Control League took on the more familiar name Planned Parenthood Foundation and continued the drive to eliminate laws restricting the distribution of information regarding contraception. It also raised money for scientific research into contraceptives. In the 1950s Sanger played a central role in raising the necessary funds and bringing together the key scientists who ultimately developed The Pill.

The developments of The Pill is widely viewed as one of the most important developments in the history of women’s rights in the U.S.

News of The Pill’s approval by the FDA on May 9, 1960 came to eighty-year old Margaret Sanger as she was having a quiet breakfast in her Tucson, AZ home. As son and granddaughter remembered the event, Sanger just sighed and said, “It’s certainly about time.” Then suddenly smiling, she said, “Perhaps this calls for champagne.”

Sanger remained active in the cause until her death in 1966 at the age of 87. By then the debate over women and reproductive rights had shifted to the more contentious ground of abortion rights.

Sources and Further Reading:

Jean H. Baker, Margaret Sanger: A Life of Passion (Hill & Wang, 2011)

Ellen Chesler, Woman of Valor: Margaret Sanger and the Birth Control Movement in America (Simon & Schuster, 2007)

Linda Gordon, The Moral Property of Women: A History of Birth Control Politics in America (University of Illinois Press, 2007).

Margaret Sanger, The Autobiography of Margaret Sanger (Norton, 1938)

Andrea Tone, Devices and Desires: A History of Contraceptives in America (Hill & Wang, 2002)