InThePastLane.com by Edward T. O’Donnell

On October 5, 1930, Fr. Charles E. Coughlin delivered his first nationally broadcast radio address. Given the strength of anti-Catholic sentiment still prevalent in the United States, it was an extraordinary moment for Irish America. Within a few months Coughlin would become one of the most widely known and influential voices in the depression-ravaged nation. His weekly broadcasts on the economy and social policy would play a key role in popularizing the idea that only radical policies could overcome the economic crisis – a sentiment that paved the way for the New Deal a few years later. And yet, Fr. Coughlin had a dark side that would later emerge and overshadow these earlier, impressive years.

Charles E. Coughlin was born in Hamilton, Ontario in 1891, the descendant of immigrants from County Cork. His father worked on the boats and waterfronts of Lake Ontario, but earned enough to ensure his only child a solid education. Coughlin entered the seminary and was ordained a priest in 1916. His first joined the faculty at Assumption College in Sandwich, Ontario where he taught English, Greek, and History.

In 1923, he requested a transfer to regular parish duty and was sent to nearby Detroit. After three years of itinerant parish work, he was chosen to organize a new parish, the Shrine of the Little Flower (named for the recently canonized St. Therese), in Royal Oak, a suburb near Detroit. The parish consisted of just 32 families and it struggled to remain financially solvent. Worse, it faced bitter denunciation from evangelical Protestants and the local chapter of the KKK burned a cross in front of the church.

The resourceful Coughlin decided to turn his troubles to his advantage. He arranged to have Detroit radio station WJR broadcast a speech detailing his struggle against bankruptcy and bigotry. On Sunday October 17, 1926, speaking from the altar of his humble church, the thirty-four year old Coughlin delivered a rousing address denouncing religious hatred and the KKK. Possessing a powerful baritone voice and years of experience as a public speaker, he proved an instant hit. When letters of praise poured in from all over Michigan, WJR gave Coughlin a regular Sunday time slot, making him the first Catholic “radio priest.”

Coughlin’s weekly addresses became more popular every week. In January 1927 he conducted the first ever mission and novena on the air and mail poured in from two-dozen states. Coughlin quickly organized these followers into his Radio League of the Little Flower. Their one dollar per year contributions to help keep Coughlin’s parish solvent and defray the cost of his broadcasts brought in $500,000 by 1929, allowing Coughlin to built a massive Shrine of the Little Flower, replete with his own radio broadcasting studio.

Then came the Great Depression. By 1930 a quarter of the nation’s workforce was unemployed and thousands of businesses and banks in tatters. While the nation’s political leaders struggled to comprehend the magnitude and meaning of the crisis, Coughlin strode into the national spotlight. He switched from speaking on purely religious topics to addressing social issues and became a fiery populist orator unafraid to denounce those whom he deemed responsible for the economic turmoil: greedy bankers, heartless industrialists, and cowardly politicians. “[B]oth the laboring and agricultural classes of America,” he told his listeners, “are forced to work for less than a living wage while the owners of industry boastfully proclaim that their profits are increasing.” He railed at Wall Street, oil companies, President Hoover, and Prohibition, and called upon the federal government to abandon laissez-faire in favor of a program to boost employment and regulate big business.

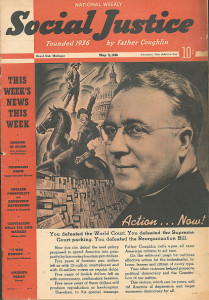

In addition to his weekly broadcast, Coughlin reached a vast audience with his publication, Social Justice.

By early fall 1930 Coughlin landed a contract with the CBS radio network. It aired his first nationally broadcast weekly address on October 5, 1930. Soon Coughlin was known from coast to coast. His mail topped 80,000 letters per week, necessitating the hiring of dozens of clerks to handle it.

Although Coughlin in these early years enjoyed wide appeal among Protestant and Jewish Americans, the foundation of his following was Catholic, especially Irish Catholic. In the decades leading up to the Great Depression, millions of Irish Catholics had climbed steadily up the socioeconomic ladder into the middle class. Because this status was so recently won, they were among the hardest hit in the wake of the Crash of 1929. Their turmoil left them looking for a leader – one of their own — who could help them make sense of their situation. As historian William Shannon described it, “Fr. Coughlin provided Irish Catholics during the crisis of the depression with a religious justification for their strongly felt but intellectually undefined impulses toward radicalism and rebellion … He made religion suddenly and sharply relevant by drastically emphasizing the socially revolutionary aspects of Christian teaching.”

Coughlin’s stock among Irish Americans rose even further with the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932. Coughlin’s vague pronouncements about government programs to boost employment and a major reform of the banking system seemed prophetic when FDR rolled out the New Deal agenda. But FDR was wary of the fiery priest and though he met with him on several occasions, he kept him at arm’s length. Coughlin in turn enjoyed his role as populist too much to throw his unconditional support to FDR and the New Deal. Indeed, by 1935 he became increasingly critical of the president’s reform agenda and cast his support to the populist Huey Long of Louisiana. After Long was assassinated, Coughlin helped found a third party, the Union Party, to challenge FDR in 1936.

By this time Coughlin had begun to express growing admiration for fascist governments of Hitler and Mussolini and a not-so-subtle anti-Semitism in his incessant denunciation of “international bankers.” In 1938, as Hitler’s anti-Semitism became more aggressive and overt, so too did Coughlin’s. “Must the entire world go to war,” he asked, “for 600,000 Jews in Germany who are neither American, nor French, nor English citizens, but citizens of Germany?” In addition to uttering more explicit anti-Jewish statements, Coughlin publicly praised and encouraged support for a rightwing paramilitary organization called the Christian Front. Many chapters, especially those in New York and Boston, engaged in anti-Jewish campaigns such as boycotting Jewish-owned businesses. They took inspiration from statements by Coughlin like, “When we get through with the Jews in America, they’ll think the treatment they received in Germany was nothing.”

By this time Coughlin had begun to express growing admiration for fascist governments of Hitler and Mussolini and a not-so-subtle anti-Semitism in his incessant denunciation of “international bankers.” In 1938, as Hitler’s anti-Semitism became more aggressive and overt, so too did Coughlin’s. “Must the entire world go to war,” he asked, “for 600,000 Jews in Germany who are neither American, nor French, nor English citizens, but citizens of Germany?” In addition to uttering more explicit anti-Jewish statements, Coughlin publicly praised and encouraged support for a rightwing paramilitary organization called the Christian Front. Many chapters, especially those in New York and Boston, engaged in anti-Jewish campaigns such as boycotting Jewish-owned businesses. They took inspiration from statements by Coughlin like, “When we get through with the Jews in America, they’ll think the treatment they received in Germany was nothing.”

As early as 1936 Coughlin faced a mounting effort by the Roosevelt administration, Vatican officials, and major political and religious figures to drive him off the airwaves. But despite tightened broadcasting regulations, Coughlin managed to air on the air. But increasing numbers of stations, responding to public pressure, began to drop his broadcast. By the outbreak of World War II in 1939 Coughlin’s rapidly shrinking audience finally led to the demise of his radio program in 1940. Two years later, his newspaper Social Justice ceased publication and Fr. Coughlin retreated into permanent obscurity. He retired in 1966 and died in 1979.

Coughlin’s long gone, but the two traditions he helped establish — broadcasting of religion and extremist politics — continue on the radio, television, and the web.

Sources and further reading:

Alan Brinkley, Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin, & the Great Depression (Vintage, 1983)

Ronald H. Carpenter, Father Charles E. Coughlin (Greenwood, 1998),

David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 (Oxford, 1999)

Sheldon Marcus, Father Coughlin: The Tumultuous Life of the Priest of the Little Flower (Little, Brown, & Co., 1973)

William V. Shannon, The American Irish: A Political and Social Portrait (MacMillan, 1963)

Donald Warren, Radio Priest: Charles Coughlin, The Father of Hate Radio (Free Press, 1996)