InThePastLane Edward T. O’Donnell

Given the raging debate in contemporary American politics over what role if any the government should play in the economy, it’s always instructive to look to history for some insight. One of the oldest and most influential myths in American history goes as follows: Before the 20th century the nation’s state and federal governments adhered to a laissez-faire creed and played no role in the economy other than to enforce the law and keep the peace. While it certainly is true that the government played less of a role in earlier eras compared to now, the notion of some past golden age of libertarian rugged individualism is, simply put, a fantasy.

We need only look to the story of the Erie Canal, which celebrates its 187th anniversary this week. This monumental feat of political will, engineering genius, and backbreaking labor was made possible only by the actions of the state government of New York. As such, it provided a model of public-private partnerships that endure to this day (consider the government’s recent role in not only creating the Internet, but also taking measures to provide nearly universal access to it). The ethos behind such ventures has remained unchanged: government investment in certain large-scale enterprises (postal service, public schools, railroads, electricity, highways, etc.) will benefit society at large.

The Erie Canal, which opened on October 26, 1825, was the brainchild of Governor DeWitt Clinton. He was in every respect the “father” of the Erie Canal. The descendant of Irish immigrants, Clinton was born in 1769 in Little Britain, NY. Educated at Columbia College, he followed the example of his uncle, then governor of New York, and entered politics. He served in the state legislature and one term in the U. S. Senate before winning his first term as Mayor of New York City in 1803. He served in that office until 1815 and won election as Governor in 1817.

Clinton was no mere politician. He was a brilliant visionary who foresaw New York’s greatness as the Empire State long before most of his contemporaries. He was also a progressive who believed – to the horror of his conservative counterparts – that the proper role of government was not merely to administer the laws and keep the peace. Rather, it was also obligated to support bold initiatives that would benefit the public, everything from public schools to a massive canal across upstate New York.

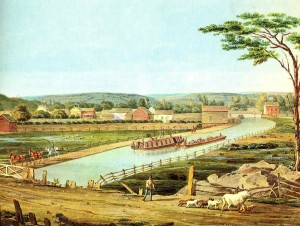

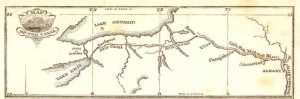

The proposed Erie Canal would run 363 miles across upstate New York, from Albany on the Hudson River to Buffalo on Lake Erie.

The proposed Erie Canal was a mind-boggling 363 miles in length across upstate New York, connecting the Hudson River with Lake Erie. It also carried a staggering price tag of $7 million. Not surprisingly, given its unprecedented size and cost, the canal generated vehement political opposition. Opponents sneered that “Clinton’s ditch” would bankrupt that state treasury and never succeed. Undaunted, Clinton waged a ceaseless campaign to garner support and in 1817 the state legislature passed a bill approving of the project.

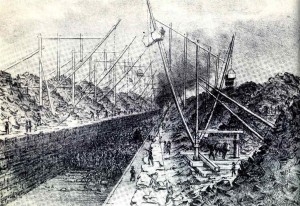

Construction began that same year. Two aspects of the project merit special attention. First, nearly all the power to dig the 363-mile canal came from human beings wielding shovels and picks (the rest came from mules and oxen). Second, since no canal of this type and size existed in the world, the project’s engineers had to invent and innovate as they went along.

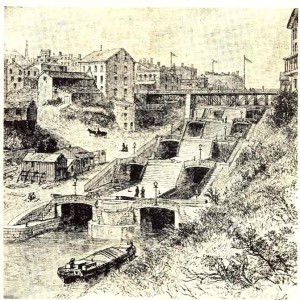

Most of the canal workers were Irish immigrants and by 1818 some 3,000 Irishmen were swinging picks and lifting shovels in the big ditch by 1818. They lived a rough existence to say the least, working long hours in exceedingly dangerous conditions for paltry wages. Scores died in construction accidents or from disease contracted in the grim canal camps. Despite these conditions, contractors never lacked for laborers and the monumental project reached completion in the fall of 1825. It took just eight short years using to dig a canal 40 feet wide and 363 miles long with 77 locks and 18 aqueducts. No project would rival it in scale, cost, and engineering challenge until the Interstate Highway program of the 1950s.

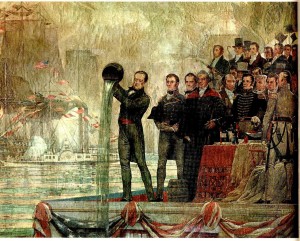

Governor DeWitt Clinton pours water from Lake Erie into New York harbor during the “Wedding of the Waters” celebration marking the opening of the Erie Canal.

To mark its opening, New York officials staged a massive statewide “Festival of Connection” that began with Gov. Clinton and a host of dignitaries boarding a canal boat in Buffalo, NY on October 26, 1825. Ten days later, after traveling the length of the canal and then down the Hudson River, they arrived in New York City to one of the most spectacular civic celebrations in the city’s history. Clinton marked the “wedding of the waters” by emptying two barrels of Lake Erie water into the Atlantic ocean.

New Yorkers were justifiably proud of their new canal, but one vital question hung in the air: was it worth it? Clinton, of course, had no doubts. On the evening of the great celebration he boasted of New York that “the city will, in the course of time, become the granary of the world, the emporium of commerce, the seat of manufactures, the focus of great moneyed operations. And before the revolution of a century, the whole island of Manhattan, covered with inhabitants, will construe one vast city.”

Proof of Clinton’s prescience was not long in coming. Within a year canal boats transported some 221,000 barrels of flour and 435,000 gallons of whiskey, to name but a few of the leading products floating on the waterway. More astonishing than volume were the speed of transit and reduction in cost. The cost of moving Midwestern grain from Lake Erie to New York harbor dropped from $100 per ton to $9 per ton. The time of transit was similarly slashed from 20 days to 7. So much commerce moved along the canal in its first nine years that toll receipts paid off the entire debt and began to finance thirteen more canals in the state.

The stunning success of the Erie Canal touched off a frenetic era of canal building that saw nearly every state in the Union launch canal projects from Massachusetts to Louisiana. Unfortunately for these states, few of these canals proved a worthwhile investment because even as they constructed them a new technology—the railroad—was rapidly taking hold. Unlike canals, the railroad could be built quickly and almost anywhere. And railroads never froze in the winter. As a result, the canal played a role in the transportation revolution that was very similar to the ill-fated 8-track tape in the 1970s. For all their limitations, 8-tracks represented the first major break from LP records, allowing people to play music of their choosing in their cars and at the beach. They were soon replaced by the far superior cassette tape (the railroad) which in turn was replaced by the compact disk (the automobile).

The Erie Canal remained a key commercial highway into the late 19th century. But competition from railroads and later trucks (neither of which froze in the winter) doomed it to sharply reduced capacity by 1900 and obsolescence by the late 1940s. Today the canal is a National Heritage Corridor with many of its adjacent towns investing in museums, historic sites, and heritage tourism designed to lure visitors and boost local economies hit hard by the canal’s demise and the loss of manufacturing.

The story of the Erie Canal reminds us that, contemporary political rhetoric aside, government investment in projects intended to benefit most Americans has a long and storied history. It’s an imperfect history, to be sure, with its share of failures, but also with its many triumphs.

Follow me on Twitter @InThePastLane

Sources and Further Reading

Peter L. Bernstein, Wedding of the Waters: The Erie Canal and the Making of a Great Nation (Norton, 2006)

Evan Cornog, The Birth of Empire: DeWitt Clinton and the American Experience, 1769-1828 (Oxford, 2000)

L. Ray Gunn, The Decline of Authority: Public Economic Policy and Political Development in New York (Cornell University Press, 1988)

Gerard Koeppel, Bond of Union: Building the Erie Canal and the American Empire (Da Capo Press, 2009)

Ronald E. Shaw, Canals For A Nation: The Canal Era in the United States, 1790-1860 ((University Press of Kentucky, 1993)

Carol Sheriff, The Artificial River: The Erie Canal and the Paradox of Progress, 1817-1862 (Hill and Wang, 1997)