This week at In The Past Lane, the American History podcast, we learn about Fred Korematsu, the courageous young man who in 1942 stood up the US government to oppose Japanese Internment during World War II. He ultimately lost his case, which went all the way to the US Supreme Court. But over time, as the nation eventually confronted the terrible harm done by Japanese Internment, Fred Korematsu was vindicated. He dedicated the rest of his life to fighting for civil rights.

This week at In The Past Lane, the American History podcast, we learn about Fred Korematsu, the courageous young man who in 1942 stood up the US government to oppose Japanese Internment during World War II. He ultimately lost his case, which went all the way to the US Supreme Court. But over time, as the nation eventually confronted the terrible harm done by Japanese Internment, Fred Korematsu was vindicated. He dedicated the rest of his life to fighting for civil rights.

And we also take a look at some key events that occurred this week in US history, like the 1960 civil rights sit-ins in Greensboro, NC and the 1990 opening of the first McDonald’s fast food restaurant in the Soviet Union. And birthdays, including –

Jan 30, 1882: Franklin D. Roosevelt

Jan 30, 1909: Saul Alinsky

Jan 31, 1919: Jackie Robinson

Feb 1, 1902: Langston Hughes

Main Story: Fred Korematsu and the Fight Against Internment

On May 30, 1942, 23-year old Fred Korematsu was walking with his girlfriend on a street in San Leandro California. A police officer approached, asked to see his papers, and then announced he had to come with him to the police station for questioning. Hours later Korematsu was arrested for violating a federal law that mandated that all persons of Japanese ancestry voluntarily surrender to the government to be sent to internment camps.

Just six months earlier, the United States Naval base at Pearl Harbor Hawaii had been attacked by Japanese forces, plunging the US into World War II. It also plunged it into a fit of racist fear and paranoia about Japanese Americans. Baseless rumors, many of them put forth by government officials and spread by the media, suggested that Japanese Americans could not be trusted – that they were likely loyal to the enemy Japanese government and therefore posed a security threat.

And so on February 19, 1942, just 10 weeks after Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 that called for all persons of Japanese ancestry to be sent to so-called Relocation Centers for the duration of the war.

Significantly, even though the US was also at war with Germany and Italy, no such relocation order was applied to Americans of German or Italian ancestry.

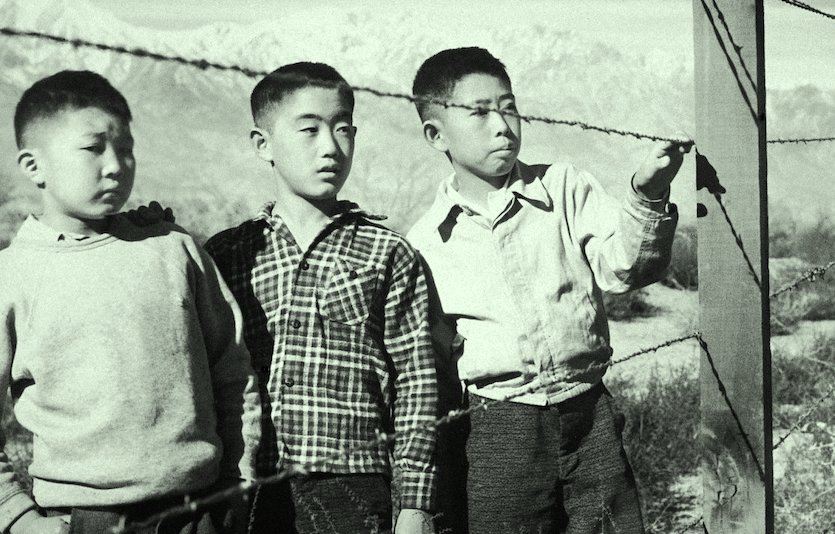

Leaders in the Japanese American community urged cooperation. They argued that resistance to internment would only validate claims by white Americans that they were disloyal. And so in the coming months, more than 110,000 people – a majority of them American citizens – were sent to one of 10 internment camps, each surrounded by barbed wire and patrolled by armed guards.

Leaders in the Japanese American community urged cooperation. They argued that resistance to internment would only validate claims by white Americans that they were disloyal. And so in the coming months, more than 110,000 people – a majority of them American citizens – were sent to one of 10 internment camps, each surrounded by barbed wire and patrolled by armed guards.

Many Japanese Americans lost everything – their homes, businesses, and farms. – and never recovered from it. They also experienced humiliation and a sense of rejection by their country. As Korematsu put it, “I lost everything when they put us in prison. I was an enemy alien, a man without a country.”

It was one of the greatest violations of civil liberties in American history.

And that’s the way an attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union saw it at the time. Ernest Besig read about Fred Korematsu’s case and went to visit him in jail. He asked him: Would you be willing to fight your conviction? Even all the way to the supreme court if necessary? Yes, said Fred Korematsu.

As he later recalled thinking, “I was an American citizen, and I had as many rights as anyone else.”

Besig filed a case on June 12, 1942, arguing that executive order 9066 violated the constitutional rights of Japanese Americans because it was based on racism. The state court summarily rejected their effort to overturn Korematsu’s earlier guilty verdict. So they appealed in federal court and lost again. The last stop was the US Supreme Court. The High Court heard the case in October, and issued their ruling on December 18, 1944. By a margin of 6-3, the majority rejected Fred Korematsu’s appeal and upheld the constitutionality of internment, saying it wasn’t motivated by racism, but rather “military necessity.”

While the decision was disappointing, the three dissenting justices – doubtless recognizing that this case, Korematsu versus US, would one day be ranked with other ignominious Supreme Court decisions like Dred Scott and Plessy vs. Ferguson, issued a blistering dissent.

Justice Frank Murphy wrote: “I dissent, therefore, from this legalization of racism. Racial discrimination in any form and in any degree has no justifiable part whatever in our democratic way of life.” And Justice Robert H. Jackson concurred: “The Court for all time has validated the principle of racial discrimination in criminal procedure and of transplanting American citizens. The principle then lies about like a loaded weapon, ready for the hand of any authority that can bring forward a plausible claim of an urgent need.”

Justice Frank Murphy wrote: “I dissent, therefore, from this legalization of racism. Racial discrimination in any form and in any degree has no justifiable part whatever in our democratic way of life.” And Justice Robert H. Jackson concurred: “The Court for all time has validated the principle of racial discrimination in criminal procedure and of transplanting American citizens. The principle then lies about like a loaded weapon, ready for the hand of any authority that can bring forward a plausible claim of an urgent need.”

World War II came to an end the following year, and eventually Japanese Americans were released to begin the process of rebuilding the shattered lives. Fred Korematsu get married, found work as a draftsman, and fell out of public consciousness – a forgotten civil rights hero. In fact, Korematsu told no one about his experience, including his children. They learned about his fight against Internment and his US Supreme Court case when one of them read about it in a US history textbook in school in the 1960s.

But in the 1970s, as a new generation of Japanese Americans begin to break the silence over their mistreatment at the hands of the US government – and eventually seek reparations – Fred Korematsu was rediscovered.

In 1983, with the help of a legal scholar who had unearthed a mountain of evidence about the racist motives behind internment – evidence the US government had suppressed during the trials – Fred Korematsu had his conviction overturned in federal court. He was vindicated.

Empowered by this turn of events, Fred Korematsu became a vocal civil rights activist for the rest of his life. In 1998, President Bill Clinton awarded him the presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

Fred Koremastu died in 2004.

Seven years later in 2011, the state of California named January 30 – Fred Korematsu’s birthday – as Fred Korematsu Day. It was the first instance in US history that a day had been named in honor of an Asian American. Since then, five more states have recognized named January 30 as Fred Korematsu Day.

Fred Korematsu once said, “It may take time to prove you’re right, but you have to stick to it.”

Further Reading:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fred_Korematsu

https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/fred-korematsu-arrested/

For more information about the In The Past Lane podcast, head to our website, www.InThePastLane.com

Music for This Episode

Jay Graham, ITPL Intro (JayGMusic.com)

The Joy Drops, “Track 23,” Not Drunk (Free Music Archive)

Borrtex, “Perception” (Free Music Archive)

Blue Dot Sessions, “Pat Dog” (Free Music Archive)

Jon Luc Hefferman, “Winter Trek” (Free Music Archive)

The Bell, “I Am History” (Free Music Archive)

Production Credits

Executive Producer: Lulu Spencer

Graphic Designer: Maggie Cellucci

Website by: ERI Design

Legal services: Tippecanoe and Tyler Too

Social Media management: The Pony Express

Risk Assessment: Little Big Horn Associates

Growth strategies: 54 40 or Fight

© In The Past Lane, 2020