InThePastLane November 21, 2012 Edward T. O’Donnell

Here’s a historian’s guide to getting the most out of “Lincoln.”

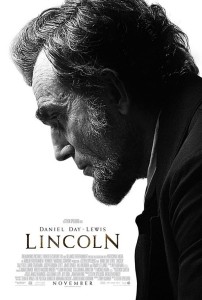

Stephen Spielberg’s latest film, “Lincoln,” has been hailed by reviewers as a masterpiece (this historian agrees). Daniel Day-Lewis’s depiction of the 16th President has likewise been described (for good reason) in rhapsodic terms. Given this hype, it’s likely that you’ll either want to go see the film, or you’ll be dragged to the theater by friends and family. To increase the chances you’ll enjoy it, here’s a quick history refresher on the context of the film.

Stephen Spielberg’s latest film, “Lincoln,” has been hailed by reviewers as a masterpiece (this historian agrees). Daniel Day-Lewis’s depiction of the 16th President has likewise been described (for good reason) in rhapsodic terms. Given this hype, it’s likely that you’ll either want to go see the film, or you’ll be dragged to the theater by friends and family. To increase the chances you’ll enjoy it, here’s a quick history refresher on the context of the film.

The film opens in late 1864 – that means the war has been going on for three and a half years. Hundreds of thousands have already died (toward a total of more than 700,000 by war’s end in April 1865). No one imagined such a prolonged and bloody war when it began in April 1861. Nor did they imagine that the war to preserve the Union would expand to become a war to eliminate slavery. Lincoln had announced the Emancipation Proclamation in Sept. 1862 and it took effect on Jan 1, 1863. The Proclamation declared free some slaves, but not all, leaving the ultimate fate of slavery unclear.

Two key issues dominate Washington, DC during this period:

Two key issues dominate Washington, DC during this period:

1) should Lincoln agree to meet with Confederate commissioners to discuss a negotiated peace?

2) can Lincoln and the more radical wing of the Republican Party pass the 13th Amendment that will abolish slavery?

To complicate matters, the two issues are intertwined. Many congressman who might support the 13th Amendment as a war measure that would demolish the southern economy, would pull back from such a radical measure if they thought a negotiated peace between North and South was imminent.

So when the Confederates send three commissioners North in early 1865 to discuss a possible negotiated peace, it puts Lincoln in a bind. He is determined to win the war and thereby preserve the Union, a goal he believes the Constitution requires of him. Having long been a foe of slavery (and in recent years warming to the idea of black equality), he is also determined to abolish slavery by seeing to the passage of the 13th Amendment. But he knows the Confederate commissioners will insist on totally unacceptable peace terms that will recognize Confederate independence (goodbye Union) and maintain slavery (moral imperative bungled). Still, Lincoln cannot outright reject the Confederate peace commissioners because the Northern public is tired of war and inclined toward accepting any negotiated settlement that will end it.

The central challenge then is: Can Lincoln keep the peace commissioners at bay long enough to gain passage (via a relentless full-court press by key Republicans to garner 30 votes in the House) of the 13th amendment?

Lee Pace plays Fernando Wood, Copperhead Congressman from New York. Copperheads were conservative Northern Democrats who sympathized with the South and bitterly opposed emancipation and racial equality.

Opposing Lincoln and the 13th Amendment are conservative Democrats (many with strong ties to the South) and conservative Republicans who are opposed to wholesale emancipation of four million slaves. It’s important to keep in mind that racism runs deep in the North in this period. While many Northerners want to end slavery because they understand that it makes a mockery of American republican ideals of liberty and equality, most adamantly reject the idea that freed slaves will live among them as equal citizens. In other words, it is possible to be both an abolitionist and a racist; to hate slavery and the enslaved. Many Northerners fit this description and they envision a post-Civil War America in which slavery continues to exist (ideally fading away over time) and where those slaves emancipated during the war are sent back to Africa.

The most vociferous opponents are Democrats known as Copperheads. The character in the film who declares on the House floor that (paraphrasing) “Congress cannot make equal those whom God himself has made unequal!” is Fernando Wood (played with exquisite malevolence by Lee Pace), the former Mayor of New York.

Tommy Lee Jones plays radical congressman Thaddeus Stevens, an advocate of not just emancipation but also full equality for blacks.

The most vociferous champion of not only emancipation but also black equality is Thaddeus Stevens (played by Tommy Lee Jones, or the dude in the wig), Congressman from Pennsylvania. He is easily the most radical man in Congress, for as noted above, many Americans opposed BOTH slavery and black equality. Stevens is a key player in the struggle for the 13th Amendment, but he’s also a huge liability because his radical views on black equality are easily demagogued by Wood and the Copperheads to scare Congressmen away from supporting the Amendment.

A few small points to be aware of:

Lincoln did indeed have a high-pitched, nasal voice as depicted by Daniel Day-Lewis.

Lincoln also loved telling stories (likewise depicted to perfection by Day-Lewis), a habit that many loved but many others (Secretary of War Stanton, played by Bruce McGill) hated.

Lincoln and his wife Mary did have a turbulent marriage, but there’s a lot of evidence that they cared for each other. Furthermore, while Mary Lincoln has long been characterized as “crazy” and a major problem for Lincoln, more recent scholarship takes a more balanced view: she appears to have been somewhat mentally unstable (perhaps even bipolar), but this condition was heightened by the strains of the presidency (during a civil war no less) and the loss of their son.